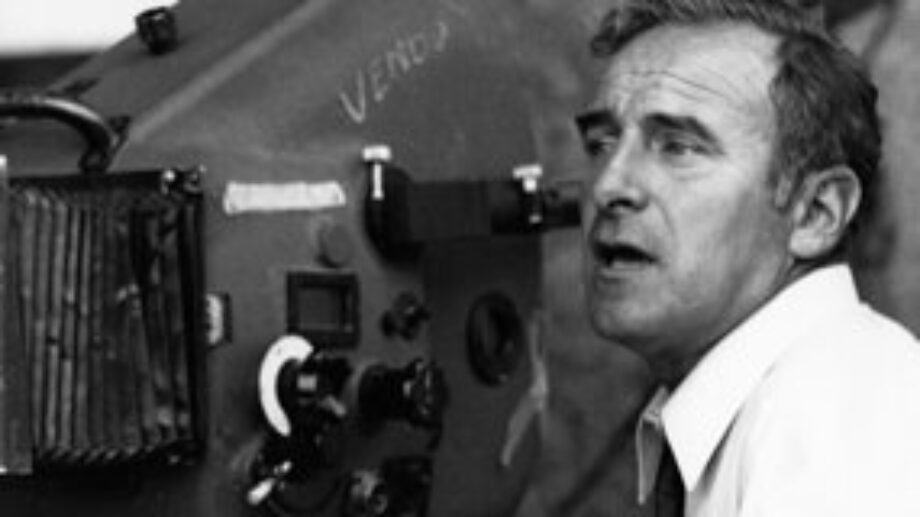

Claude Sautet

“You put in details from your own life without actually wanting to do so expressly. I recognize that I have gone through a lot of the stages described in the film. I've known ennui, I've known misogyny, I've known misanthropy. I've gone through periods where one protects oneself as though one has been living in a fortress. I've known the moments when one is uncertain about everything in life.” —Claude Sautet

Critical darling. Audience favorite. The man who made a star out of Romy Schneider and gave Michel Piccoli some of his finest roles; the man who played a large part in rescuing French cinema from its post-New Wave, post-May ’68 doldrums. Tender observer of human behavior, poet of failure, heir to a French humanist tradition stretching back to Vigo and Renoir. So why did Claude Sautet ever need rediscovering? Why is our upcoming career-spanning retrospective the first-ever complete survey of this major filmmaker’s work? Why are most of his mid-career masterpieces still not available on DVD this side of the Atlantic?

It’s not because his films don’t entertain. Classe tous risques, the first film over which Sautet had creative control, is a taut, gripping, and desperately personal film noir. Just as thrilling is his follow-up The Dictator's Guns (L'arme à gauche), a ripping high-seas yarn overshadowed on release by Sautet’s more radical New Wave contemporaries and begging to this day for rediscovery.

Nor is it because we can’t relate to his heroes. After those early commercial disappointments and a brief departure from filmmaking, Sautet returned with The Things of Life (Les choses de la vie)—and promptly became an overnight sensation. That film was, in retrospect, the first flowering of Sautet's mature style: a beautifully restrained and emotionally honest romantic drama. It also marked Sautet's first collaborations with Piccoli, playing a car-crash victim looking back over his tumultuous love life, and with Schneider, here in the role of the victim's volatile mistress.

A Heart in Winter

Piccoli and Schneider would crop up again and again in Sautet's string of subsequent triumphs: intimate, relatable, and fiercely personal portraits of middle-class life. Sautet was a truly compassionate filmmaker, never mocking his characters' bourgeois pretensions but treating their successes and failures alike with the utmost dignity. Brought to life by the same stars film after film, these characters start to feel like old friends and Sautet treats them accordingly, with respect and even love. The struggles they face are often our own: romantic entanglements in César and Rosalie (César et Rosalie), mid-life crises in A Simple Story (Une histoire simple), economic failure in Vincent, François, Paul and the Others (Vincent, François, Paul… et les autres), fraught parent-child relationships in The Bad Son (Un mauvais fils), aging, disappointment, and possibly redemption in all.

Only once would Sautet return to the crime dramas with which he first made his name, this time with a new degree of attention to the nuances and contradictions of friendship, loyalty, and love. Max et les Ferrailleurs is one of the filmmaker's finest works and yet, shockingly, its week-long run at the Film Society will mark its first-ever U.S. theatrical engagement.

Sautet would suffer one more self-inflicted exile from filmmaking in the mid-80s, following the commercial failure of his breezy restaurant-set drama Garçon! When he did return, it was with a trilogy of films that would bring him the most international acclaim of his career. The bustling, farcical A Few Days with Me (Quelques jours avec moi) set Sautet free from his increasingly burdensome reputation, setting the stage for the filmmaker's two late-career masterworks: A Heart in Winter (Un coeur en hiver) and Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud (Nelly et Monsieur Arnaud). Gentle, autumnal portraits of aging, loneliness, and the human need to create, they concluded Sautet's career-long investigation into the mysteries of human motivation in the only way possible: with a dignified but bittersweet question mark.

Claude Sautet: The Things of Life runs at the Walter Reade Theater from August 1 – 9. The majority of films screened have never been released on DVD in the U.S. This is the first-ever complete retrospective of Sautet’s work. Max et les Ferrailleurs opens August 10 for a week-long theatrical run. This is the 41-year-old film's first U.S. theatrical engagement.