With art came commerce and, if a current trend in the small screen medium is any indication, it now finds itself heading in the opposite direction.

Recently, three of the world’s most respected filmmakers—Martin Scorsese, Oliver Stone and Wes Anderson—each worked on short films designed to advertise products to the masses. For Scorsese, it was a fragrance (Dolce & Gabbana’s The One), for Anderson a company famous for leather handbags (Prada) and for Stone, a mammoth global event (the 2014 World Cup in Brazil). Working with minimal running times—the longest being Anderson’s Castello Cavalcanti at eight minutes—this opportunity brought challenges for directors accustomed to working on full-length features.

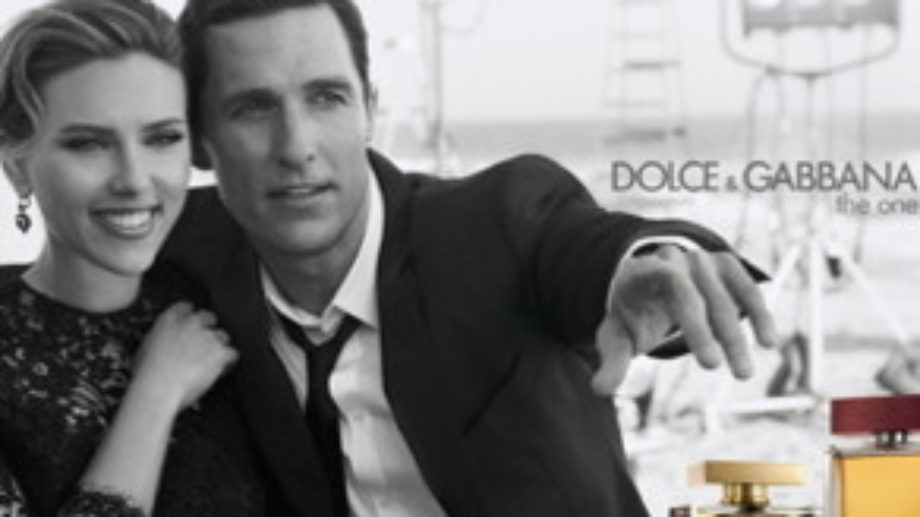

Street of Dreams, Scorsese’s black-and-white two-hander starring Matthew McConaughey and Scarlett Joahnsson, is the most alluring of the bunch, an intoxicating and vaguely mysterious romantic race-against-the-clock. Scorsese’s common storytelling cadences, such as the ever-swooping camera and the aching music from yesteryear, are on full display here.

More implied than told, the plot moves quickly. Johansson plays an in-demand model who has a plane to catch in just a few hours, but first allows McConaughey’s character to pick her up for a quick ride around New York. The two flirt and reminisce as passion, nostalgia and otherworldliness take over. “I miss this city,” the woman reflects. “Even when I’m here, I miss it. It’s always changing.” Walking up to a building, the man jokingly agrees: “Yeah, like this building. It used to be [points behind her] over there.” The two verbally engage one another before heading up top to overlook New York. Speaking on their former fling (or relationship, or something else entirely), the man asks, “What if we could go back? Would we?” “If we did, could we make it stick?” she responds. We then hear Johansson via voiceover, “Dolce and Gabbana: The One,” as the perfume bottles appear over an image of the couple.

Wes Anderson’s Castello Cavalcanti is less a commercial than a personal short film. Set in Italy in September 1955, this single-location comedy features a collection of townsfolk, sitting outside a local café, anticipating a boisterous grand prix. One unlucky driver (played by Anderson regular Jason Schwartzman) crashes his automobile right in front of them, claiming that his mechanic (who is also his brother-in-law, Gus) screwed his steering wheel on backwards! The driver takes a rest and decides to wait for the local bus. Lucky for him, his wait is a pleasurable one: he makes some new friends and gets reacquainted with people he believes to be his ancestors. He even gets to chow down on some spaghetti. This light, humorously colorful short fits the “Anderson style” to a tee and is a welcome addition to his cannon. The only sign that this is an advertisement for Prada is in the opening credits and in the driver’s outfit (“Prada Racing” is sprawled across his back).

The most explicit in its advertising and in some ways the most meta, Oliver Stone’s recent DirecTV spot promoting next year’s World Cup is both an action movie and an authorial throwback. Reminiscent of his own football movie, Any Given Sunday, here Stone casts himself as a visionary director on location at the World Cup. As this is the world’s most viewed sporting outing, Stone treats us to a common visual reference often employed to imply the global scope of an event: families and friends of all cultures anxiously watching their television sets. Stone wants “glory, more flags, more people, more passion,” and he delivers in spades; the camera, and in effect the audience, often soars alongside the ever-quickening soccer ball and the mythic, God-like creatures known as soccer players. Toward the end, the inspirational music soars as fireworks go off and the stadium erupts in earth-shaking cheers. Are you ready for the World Cup?

For fans of the three auteurs, these short pieces represent a worthwhile continuation of their efforts. Cynics could deem the works as nothing more than a device to sell a product, but in watching them, you begin to realize that these commercial endeavours provided the filmmakers with a new outlet in which to display their artistry. As inspiration can come from many sources, you'd be hard pressed to pass up an opportunity that allows for some creative playtime. In this case, the end result speaks greater than the starting point.