Teller's Tim's Vermeer

In her final installment from the recent New York Film Festival, Judith Dry takes a look at the concept of legitimacy via two films that played the event, Teller's doc Tim's Vermeer and Nadav Schirman’s In The Darkroom.

Take 2400 hours of raw material, 500-plus days of meticulous painting, and a whole lot of expendable capital and a year to whittle it down to 80 minutes, and you have Penn & Teller’s wildly entertaining new documentary, Tim’s Vermeer. The magicians have waved their wands, and pulled a Vermeer colored rabbit out of their hats.

That’s Johannes Vermeer, the seventeenth-century Dutch painter, but he’s not in the movie. The film's main character is Tim Jenison, founder of NewTek, Inc. and inventor of visual imaging computer software. Not only is Tim a tech genius, his success affords him the time and money to play around with things like trying to paint a Vermeer. Oh, and strapping a fan to his back while roller skating.

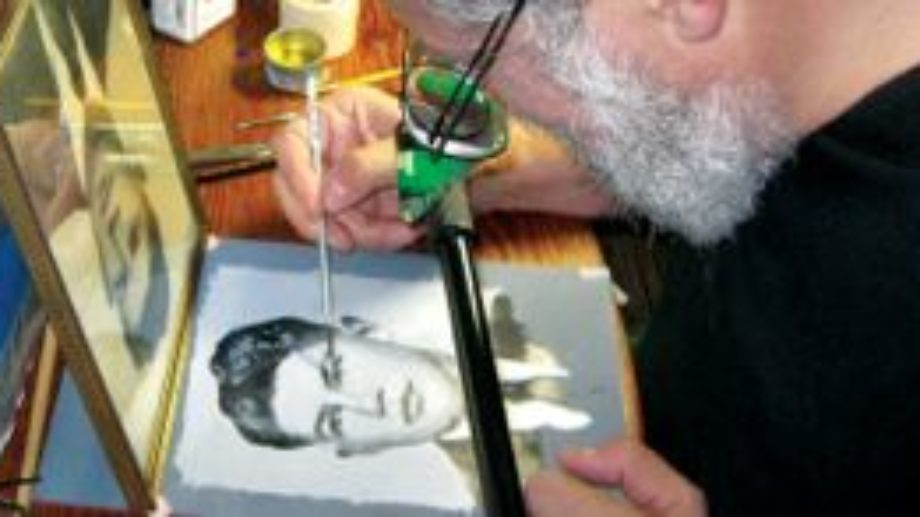

Jenison has a theory, also touted by David Hockney (who appears in the film), that Vermeer used a camera obscura to create his luminescent masterpieces. Not only that, he expounds on this theory to suggest Vermeer lined up a tiny mirror with the canvas and painted the colors he saw in the mirror. Essentially, he thinks Vermeer painted by numbers. Naturally, many art historians decry this theory as blasphemy, but Jenison genuinely admires Vermeer – obsessively so. His intention is not to discredit the artist, but merely to honor him by understanding his methods.

The endeavor unfolds like a wacky whodunit, with Jenison as the bumbling detective; so singular in his mission the viewer cannot help but go along for the ride. He painstakingly recreates a life size version of Vermeer’s The Music Lesson, and then sits down to paint it all stroke by stroke. He even uses his daughter as a model; in her corset and fontagne she is the spitting image of the girl in the painting, minus the diet coke she sips gingerly. “This project is a lot like watching paint dry,” Jenison sighs. Fortunately, watching Jenison watch his paint dry proves entirely thrilling.

Nadav Schirman’s In The Darkroom

Forgeries in the name of science as a pet project don’t carry quite the same heft as those done for terrorism. In the Darkroom is Nadav Schirman’s bleak portrait of Magdalena Kopp, the third wife of Illich Ramirex Sanchez, aka Carlos the Jackal, the notorious Venezuelan terrorist widely immortalized in many films, including an excellent 2010 mini-series by Olivier Assayas. The film gets its title from the setting for its main interviews. Kopp, a photographer who specialized in forging documents for the terrorist cell, recounts her harrowing tales under the red light of her darkroom. (Analogies to filmmaking were not evident.) Gaunt and glum and looking older than her age, Kopp asks herself, “How far would I go for my ideals? What were my ideals? Did I have any?”

This becomes the film’s central question, in interviews with retired associates and eventually, in an emotional interview with Rosa Kopp, Magdalena’s daughter by Carlos. Kopp answers for herself fairly succinctly, claiming as a soldier she had to obey orders while also admitting she feels guilt. In an unsurprising but sad revelation that their relations essentially began with rape (“I won’t say that word”), I did feel some sympathy for Kopp. But did I care? To her credit, Schirman offers an opposing view from Hans-Joachim Klein, who participated in the 1975 attack on the OPEC headquarters in Vienna but later defected. In his meeting with Rosa he calls Kopp “Mrs. Grimm” for the “fairy tales” she tells in her book.

In a shift of focus, Rosa becomes the protagonist for the final third of the film, as Kopp is suddenly moved from the darkroom and shown jogging and cutting vegetables. 'Look—She’s just a Mom now!' The film proclaims. But I’m not buying it. Schirman’s access to a notorious terrorist’s closest associates ensures that In The Darkroom will be fascinating to Carlos fanatics itching to see their aged legends onscreen. Rosa's trip to Palestine to meet her father’s contact there should feel mildly tense if not downright suspenseful, but thankfully she’s a level-headed girl and her father’s body count allows only enough room for insight along the lines of, “maybe he helped a few people after all.”