[Editor's Note: FilmLinc Daily first published this interview with Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq filmmaker Nancy Buirski in October during its World Premiere at the New York Film Festival. The film begins its theatrical run at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center at Film Society starting Wednesday. Screening and ticket information as well as planned post-screening Q&As can be found here.]

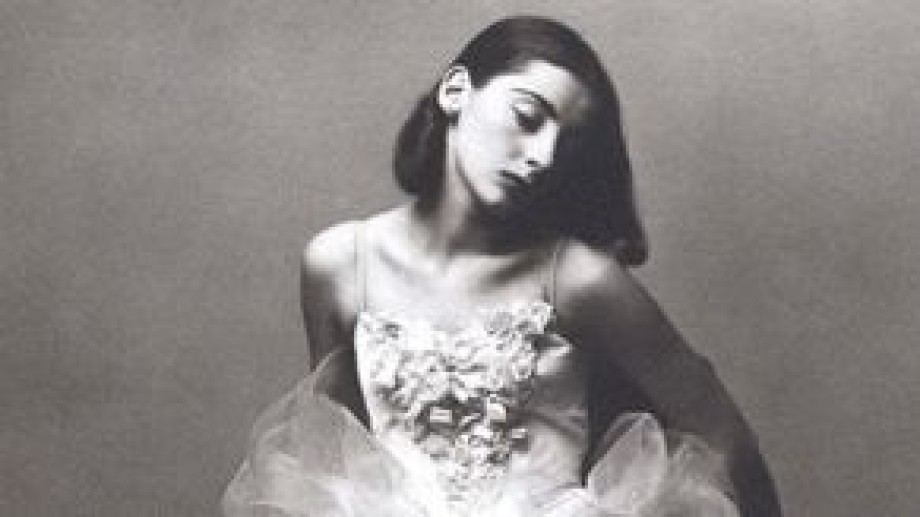

A giant in dance, Tanaquil Le Clercq transcended talent on the stage with her extraordinary movement. She mesmerized audiences and choreographers alike with her stage personality until it all came to an abrupt end much too quickly.

Known familiarly as “Tanny” by those who knew her, she became the muse of two of the greatest choreographers in dance, George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. She and Balanchine later married, while Robbins created his most famous version of Afternoon of a Faun for her. Adored, famous and widely considered the greatest dancer of her day, her life dedicated to the art of movement came to an abrupt end at the age of 27 when she was struck with polio and virtually paralyzed.

Director-producer Nancy Buirski brings Tanaquil Le Clercq's story to the screen in Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq, which had its World Premiere at the New York Film Festival. With a montage of visuals, soundtrack and dance, the Peabody Award-winning filmmaker of The Loving Story (HBO) presents a candid portrait of an artist. Buirski spoke with FilmLinc Daily ahead of the film's premiere about her discovery of Tanny, taking the story to Martin Scorsese and how founding a documentary film festival has helped inform her filmmaking.

FilmLinc Daily: From your point of view, what are some of the extraordinary aspects of Tanny and what attracted you to this story?

Nancy Buirski: Before I even her story and the compelling nature of her – in some ways – tragic story, I was simply seduced by her as a dancer and a bouffant. She appeared so extraordinary to me the way she carried herself physically and emotionally. What came through in her dance was unlike anything I had seen in dance before, and I had followed dance over many years.

FD: For a layman of dance who can appreciate it as an art but maybe loses some of the nuances that perhaps she possessed, what was that extra star quality she had that was perhaps a rarity?

NB: I think it's the personality that comes through. She was quite seductive though many dancers do emote on stage, she communicates a story. Her face and her body are seductive, sensual and full of personality in my opinion, so you're not just watching her dance – you're watching her “be.”

FD: Before embarking on this, you had seen a film that featured a segment on her. Was that a precursor to Afternoon Of a Faun?

NB: Yes, the film by Jerome Robbins called Something To Dance About. He was so captivated by her himself. There's a small chapter on her, maybe two or three scenes. There's a little bit of Faun in there and some other dances. I was literally off the seat. When watching it, I remember physically moving forward because I couldn't believe what I was seeing. And then I found out what happened to her and I thought, “oh my god,” how is it that I didn't know this story? I started to just watch her dance and was captivated by the dance. They ended the segment explaining that she suffered from polio, and I thought, “well this is just an extraordinary story.” I was already in love with her. It is a love because when you spend [several] years on a project, you have to love it. And I was taken with her.

FD: So going in what were some of the perimeters you set for yourself in telling her story?

NB: I knew it would be heavily archival. I made The Loving Story and when I did that, I had committed myself to doing it before I knew what was available and I could have been in big trouble. I was very fortunate to come across archival footage which became a part of the movie. So I decided I was going to search this out before going into it. I was very fortunate that [producer] Ric Burns decided to come on board early and help me to do that research. So that put me in the position with the dance footage. And actually before Ric Burns joined I met Barbara Horgan, who was Balanchine's assistant for many many years. Barbara got very excited by this. She told me that Tanny was a very private person. They were very good friends and had never really wanted anything done on her, which is probably why there hasn't been much done. But Barbara felt strongly that it was time and that she deserved it and had an important story to tell, so she told me that she was going to help me to do this.

So I'm indebted to Barbara for helping me move this forward. And then Ric of course. Once we had the footage, I started showing it to Martin Scorsese and he got very excited about the film too. And David Tedeschi, one of his editors, came on board to do a 12 minute trailer. And that's what interested American Masters. They were interested and that made it easier. I'm not saying it was easy after that, we still had to raise more money.

FD: Was Martin Scorsese familiar with her story?

NB: Not at all. He kind of fell in love with her the way I did. We were both fascinated with how someone adjusts to a situation like polio. We talked about the ability for someone to accept something like this, but not necessarily triumph over it, but to reconcile oneself to it and still have your life. That's what is so essential to me about Tanny's story. Tanny didn't change. Her personality didn't change.

FD: You had access to the letters that were read, which were surprising on a certain level because there was a level of acceptance of her polio. Of course writing a letter doesn't necessarily get entirely inside one's psyche, but the letters revealed in your film show not exactly a comfort, but that she's dealing with it…

NB: Yes, letters can be a little misleading. She was probably writing when she was in a bit of a better mood. There were letters that revealed a bit of her depression and she did remain depressed for many years, but she tried to come out of it for many years through her letters. I think the correspondence she had with Jerome Robbins and a few others she wrote to on a regular basis that don't appear in the film – just for cohesion purposes – were really critical to her well-being. So maybe you see a bit of a more upbeat side of her. But I think her personality comes out through these letters.

FD: How were you able to access the letters etc.?

NB: We had access through the Robbins Rights Trust and we also accessed a tremendous amount of footage and photographs through the New York City Ballet and the Jerome Robbins Foundation and the George Balanchine Trust. They opened up their archives for us.

FD: How would you describe the relationship between Balanchine and Tanny?

NB: You know, I think it's like any relationship. It's complex and there are many layers. One aspect of this story that interested me very much is the artist-muse relationship. And there's no question Balanchine fell in love with women because of how they inspired him to create dance. The interesting thing about the artist-muse relationship in dance is that the dancer also is the recipient of the relationship. In other artist-muse relationships that is not the case. The artist is the recipient and the muse is exploited, but here the dancer is complicit and recipient. So that's part of what this relationship was about and a lot of what Balanchine's other relationships were about. But I don't think it's a question of him exploiting Tanny because I think she got as much out of the relationship as he did.

I think some people might have a [negative] idea when they think an artist is exploiting his muse, but this wasn't the case. It was much more reciprocal and there are many women who get into these relationships who know what they're doing. And Tanny was a very smart woman and I think that comes through in the film.

FD: She's clearly very strong and determined. I was very happy to learn that she eventually started teaching.

NB: She's resilient. If she hadn't been depressed for a number of years, people would wonder why? If you think your entire life is going to be about the function of movement and suddenly you can't move anymore, then that has to be devastating. Tanny's whole life wasn't all about dance as it is for some dancers. She was very intellectual, spoke many languages and well read. She had relationships outside of the dance world. But still, her purpose was dance and yet she was able to summon the strength that I think were a function of those other aspects of her life that helped her get through this. She lived very much in the moment and many dancers do because they know that their careers are going to end. But in the case of Tanny, her career ended way too early.

FD: I know it's hard to speculate on what would have happened had she not gotten polio…

NB: It's hard to say. I think she would have danced for a long time. She was getting incredible response to her dance so that would have likely empowered her to dance for a long time, but she had other interests. There were times when she was tired dancing. There's that one moment in the film where she has some time off and talks about how she “doesn't get to do this anymore…” She was multifaceted, but by the way Balanchine was too. That was another aspect about doing this film. All the characters are neither all good or all bad. You see a lot of humanity come out in this film. He's not just a man that exploited a dancer by any means, he took very good care of her and worked very hard to get her to walk again. He cultivated steps for his dancers. He taught them how to dance and move. So he took that skill in teaching her how to walk again. He tries to get her to walk. So in some ways the relationship didn't change – for awhile anyway…

FD: This is slightly off the subject, but you're a founder of the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival and you have that as a background. So I'm curious if that experience has informed your approach to documentary filmmaking?

NB: Oh very much so, very much so. What it did show me is that there are many different ways to make docs. But it also reminded me that too many people adhere to rules, so I think too many docs become formulaic as a result. First time filmmakers especially feel like they have to do it a certain way in order for it to be a documentary. They think the means in which they make it defines the documentary. And I think that's too bad because they lose some of themselves in an effort to make it – I don't want to say formulaic, maybe that's too strong of a word. But I think any kind of filmmaking has to come from deep inside you. You grapple with that.

I have to admit when I came across Tanny's story, the first thing I thought of was [Julian Schnabel's] The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. I thought this is an opportunity to tell the story in a creative way. I didn't even think of documentary as much as the creative expression for this experience. How do we communicate the feeling of what she went through and not just what happened, and I realized there's a lot of ways in which to do it including through montage which we used quite a lot in this movie. So I approached it with pretty much knowing what I wanted to do. And again, it wasn't so much through documentary but communicating a feeling of what I initially thought of this as a tragic story, though I don't see it as tragic anymore. I see it as a story of hope.

FD: Obviously NYFF at Lincoln Center is a great setting to show this film…

NB: Oh, it's beyond my wildest dreams. I grew up with this festival…I started off as a painter and later photography and through Full Frame into film. I would come to this festival to see the greats of film. The first Martin Scorsese films I saw were at this festival. And I remember thinking, “There are different ways to make movies. So this is really a pinnacle I think.”