Print Screen: James Hannaham and Manji

Bridging the worlds of cinema and literature, our new recurring series Print Screen invites our favorite authors to present films that complement and have inspired their work, with discussions and book signings to follow screenings. In the next installment, novelist James Hannaham, author of the acclaimed Delicious Foods (published this March), joins us to present a screening of Yasuzo Masumura’s rare 1964 feature film Manji, with a discussion and book signing to follow. Co-presented with Japan Foundation New York.

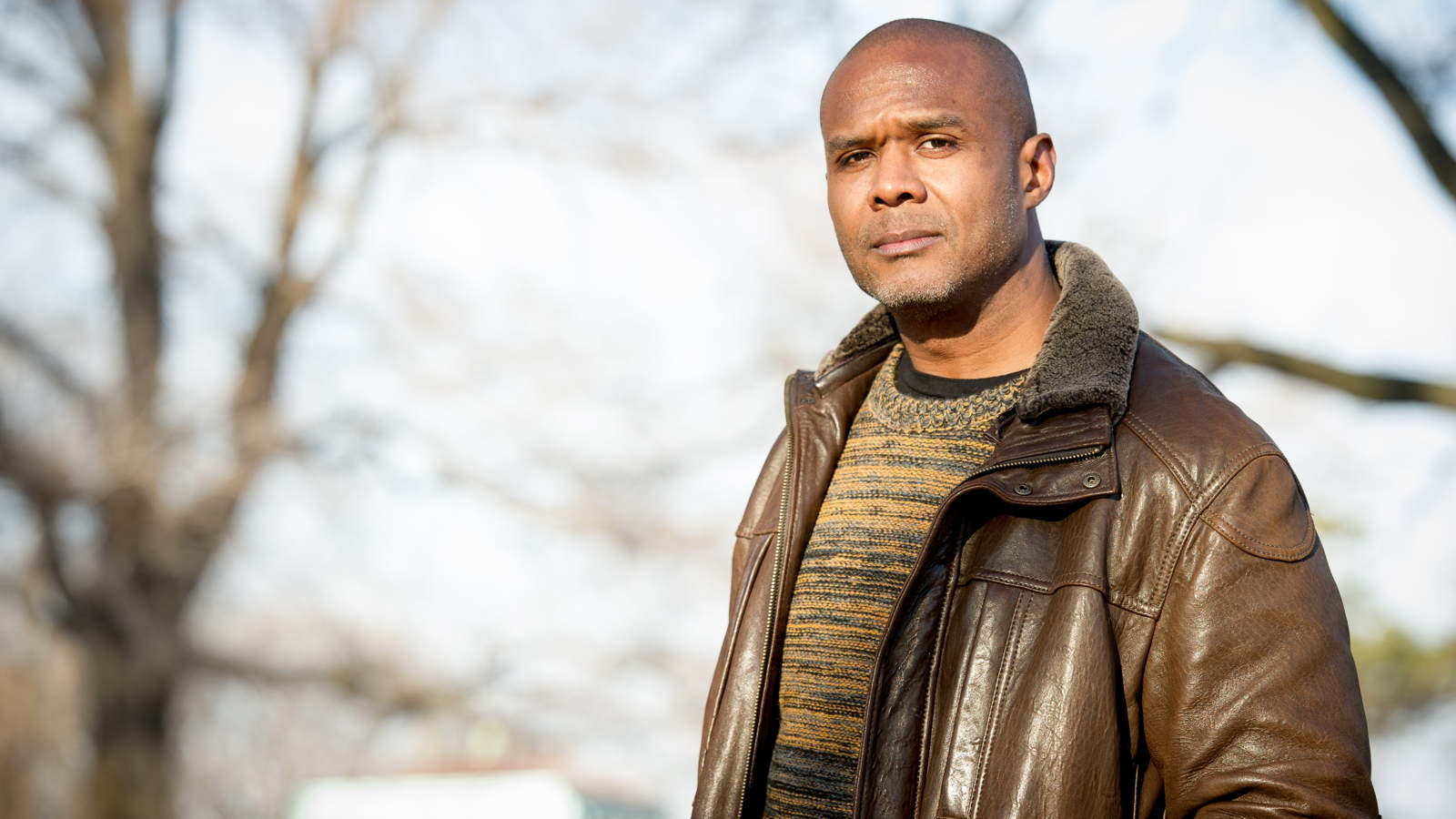

James Hannaham is the author of the novel God Says No, which was honored by the American Library Association. He holds an MFA from the Michener Center at the University of Texas at Austin, and lives in Brooklyn, where he teaches creative writing at the Pratt Institute.

Manji

Yasuzo Masumura, Japan, 1964, 35mm, 92m

Japanese with English subtitles

The bored housewife of a passionless lawyer, Sonoko (Kyoko Kishida), enrolls in a women’s art school and develops a friendship with Mitsuko (Ayako Wakao), the school’s reigning beauty, setting the stage for an intersecting, bisexual love affair between wealthy residents of Osaka. Japanese New Wave iconoclast Yasuzo Masumura rendered this lurid melodrama, based on the novel by Junichiro Tanizaki, with a liberating intensity that rebelled against Japanese social norms of the time. Exquisitely lensed by Setsuo Kobayashi (Fires on the Plain), Manji traces decadent sexuality across nude bodies that are never fully exposed, and sharp close-ups of bare skin and uncovered napes are captured through furtive glances, suggesting tactile beauty by way of material minutiae. Print courtesy of Japan Foundation New York.

James Hannaham on Manji: “Yasuzo Masumura’s sensibility, and its mixture of meticulous work, elegance, and sleaze, first captured my attention when I saw Giants and Toys (1958), a satire about two candy companies battling for PR dominance in progress-mad Japan. I expected a similar tone from Manji (1964), but I got instead an intense, almost campy, over-the-top love rhombus. The film handles the gay relationship without judgment, self-consciousness, or even politics—unheard of for movies of the time. Masumura studied in Italy with Antonioni, Fellini, and Visconti; accordingly, his movies are eye-poppingly beautiful spectacles of light and shadow, especially this one. The film’s sumptuous allure creates a wonderful tension with its lurid story, one that seems at times a powerful metaphor for Japan’s postwar seduction by and submission to Western culture. The filmmakers and artists I find most inspiring are those who successfully combine intellect, beauty, humor, and unabashed vulgarity—Luis Buñuel, Pedro Almodóvar, Kara Walker, John Waters, Jean Genet. Masumura has this kind of scope; I aspire to his level of eloquent shamelessness.”