John Zorn: A Film in 15 Scenes

John Zorn and all filmmakers in person at the October 8 screening!

|

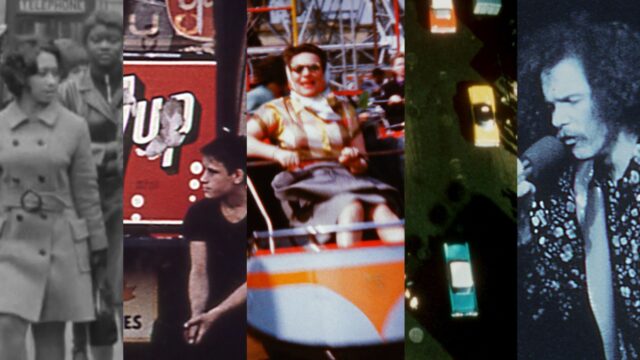

15 scenes: 254 shots Well Then There Now</a> Bare Room arcana |

Growing up I had two passions: music and film. In addition to spending a lot of time composing and improvising, I also made films, wrote screenplays and watched up to four movies a day, hanging out nightly in the New York art theaters (Thalia, Bleeker, Elgin, Bijou) the MoMA, Millennium, and the Anthology Film Archives. The choice between film and music was a difficult one—but one could say that I ultimately opted for both, as film has continued to play a very large part in my life, inspiring some of my greatest works, and deeply informing my development as a composer and as an artist.

There are many connections between music and film: the use of time, dynamics, tension and release, drama, tempo, climax, the concept of montage and the harnessing of individual performances into an organic and flowing whole. Both center around people and the idea of community, and are arts made available to the world at affordable prices. But there is also a more esoteric connection. Music and film (the visual and the aural) have always been intrinsically linked in my mind's eye/ear via synaesthesia, through which images lead to sound and sound leads to images. In some respect all of my work, from bands like Naked City, Masada and The Dreamers, to concert music like Necronomicon, Carny, La Machine de l'Etre, to my film soundtracks and perhaps most of all my file card compositions (the aural cinema of Spillane, Godard, Elegy, Kristallnacht, Duras, Femina, Dictée, Liber Novus, Interzone, Mount Analogue) are marked or driven by a strong sense of the visual.

In addition to writing a series of surrealistic screenplays and making a handful of experimental films, I have also worked directly with the visual in musical ways through the elusive Theatre of Musical Optics, which has continued in private performance since 1974. Variously described as visual music, performance art, magic and even mystic ritual, these shows are another example of my experiments in synaesthetics. A series of small objects are presented sequentially under a special light on an 8-inch square black stage. The performance usually begins at one-minute-to-midnight on Halloween, is by invitation only and limited to an audience of about 7 people. After over 35 years of performances not many more than 120 different people have seen them—including Jack Smith, Stuart Sherman, Ken Jacobs, Laurie Anderson, Richard Foreman, Mike Smith, Lyn Hejinian, Stefan Brecht, Mathieu Amalric, Michael Counts and George Macunias. The ordering of events in time is at the heart of these shows, of most of what I do, and of the screenplay upon which the four films in this program are based.

The script began in 1981, was completed in Japan some years later, and sat unrealized amongst my papers for years. In 1999 when the first Arcana volume was ready for publication it occurred to me that it might make a unique contribution to the book. Many were confused as to its inclusion. How could I tell people that I considered it to be visual music—I was already in enough trouble as it was! So I kept my mouth shut, people speculated, and years passed. In late 2005 (possibly because of the great success of the Book of Angels project in which a variety of musicians interpreted my Masada compositions) the idea came to me to reach out to my friends in the film world to commission four different versions of the shooting script.

A list of 254 shots divided into 15 scenes exploring juxtaposition and experimental narrative, the script functions very much like a musical score that can (much like the Book of Angels project) be interpreted by a variety of creative minds in surprising ways. Sometimes I can be maddeningly specific about what I am looking for (a Virgo control freak) but ultimately what I put on the page is meant to open up possibilities for the performer/interpreter, not close them down. Much of my work is about the interaction of imaginations., and the balance of what is specified and what is left for interpretation is one of the keys to making great work. To a creative mind limitations can actually lead to greater freedom, inspiring and activating the imagination in exciting new ways. It is essential for the interpreter to inject themselves into a work, investing it with breath, life and space, but it is just as essential that its form and content be respected, its integrity remain intact. Imagination tempered with understanding, respect, care, honesty, craft and passion makes great interpretation.

Henry, KimSu, Joey and Lewis are all brilliant filmmakers with strong personal styles. Each has approached the scenario using a unique visual sensibility and an original sense of drama and pacing. Joey and KimSu connected immediately to the script and completed their films in a matter of months, while Henry and Lewis took years. Although the image sequence is the same from film to film, it is remarkable how different the results, how surprising. None are even remotely like what I would have created on my own (in some ways the most successful projects are also the most surprising) and this project is filled with the kind of surprises that result from careful thought and rich imagination.

For some reason an original title for this script never really stuck, and when it was printed in Arcana it was simply called Treatment for a Film in 15 Scenes. In retrospect this was prescient—the four films here have all found their own identities through the vision of the individual filmmakers, and have been aptly titled by each director accordingly. Other directors have already expressed interest in shooting further versions of the script and a second group of films should be released in the coming years.—John Zorn