Posters into Film: Borowczyk, Lenica, and the Cartoon Renaissance

Born in Poland during the 1920s, Walerian Borowczyk trained as a painter and sculptor before establishing himself first as a poster artist and later an animation filmmaker. After relocating to France during the late 1950s, Borowczyk made his international debut with a series of films co-created with Polish graphic designer and cartoonist Jan Lenica. These startling, often comic short films were as innovative as they were provocative—pioneering in both their narrative strategies and stylistic elements (cutout and hand-painted animation), and influential to artists as wide-ranging as Terry Gilliam and collaborator Chris Marker. Borowczyk was the subject of a long overdue retrospective in 2015, and Film at Lincoln Center is pleased to continue recognizing his cinematic contributions with a special presentation of newly restored versions of these short films, as well as Konstanty Gordon’s short newsreel documentary about poster art, co-written by Borowczyk.

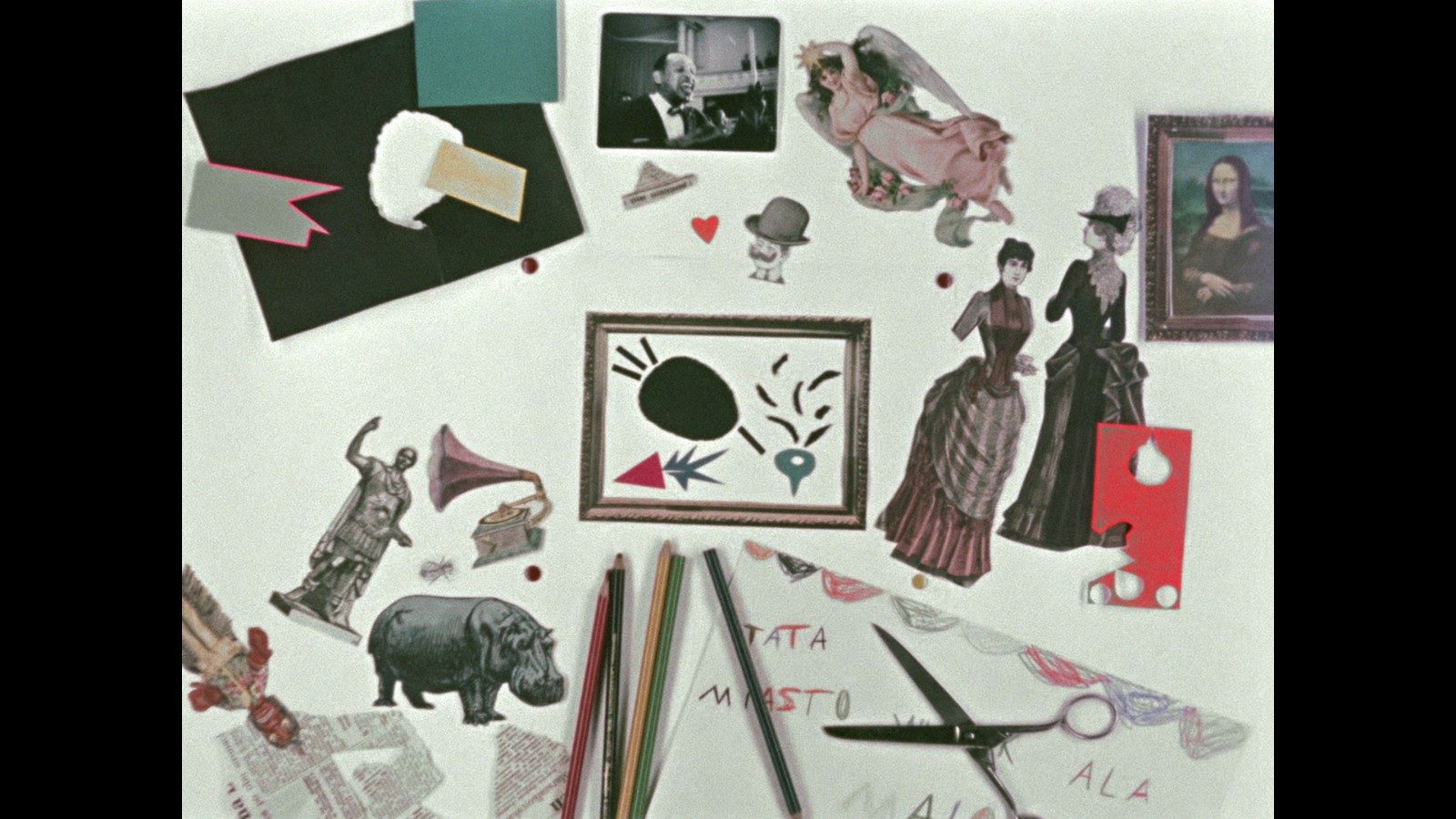

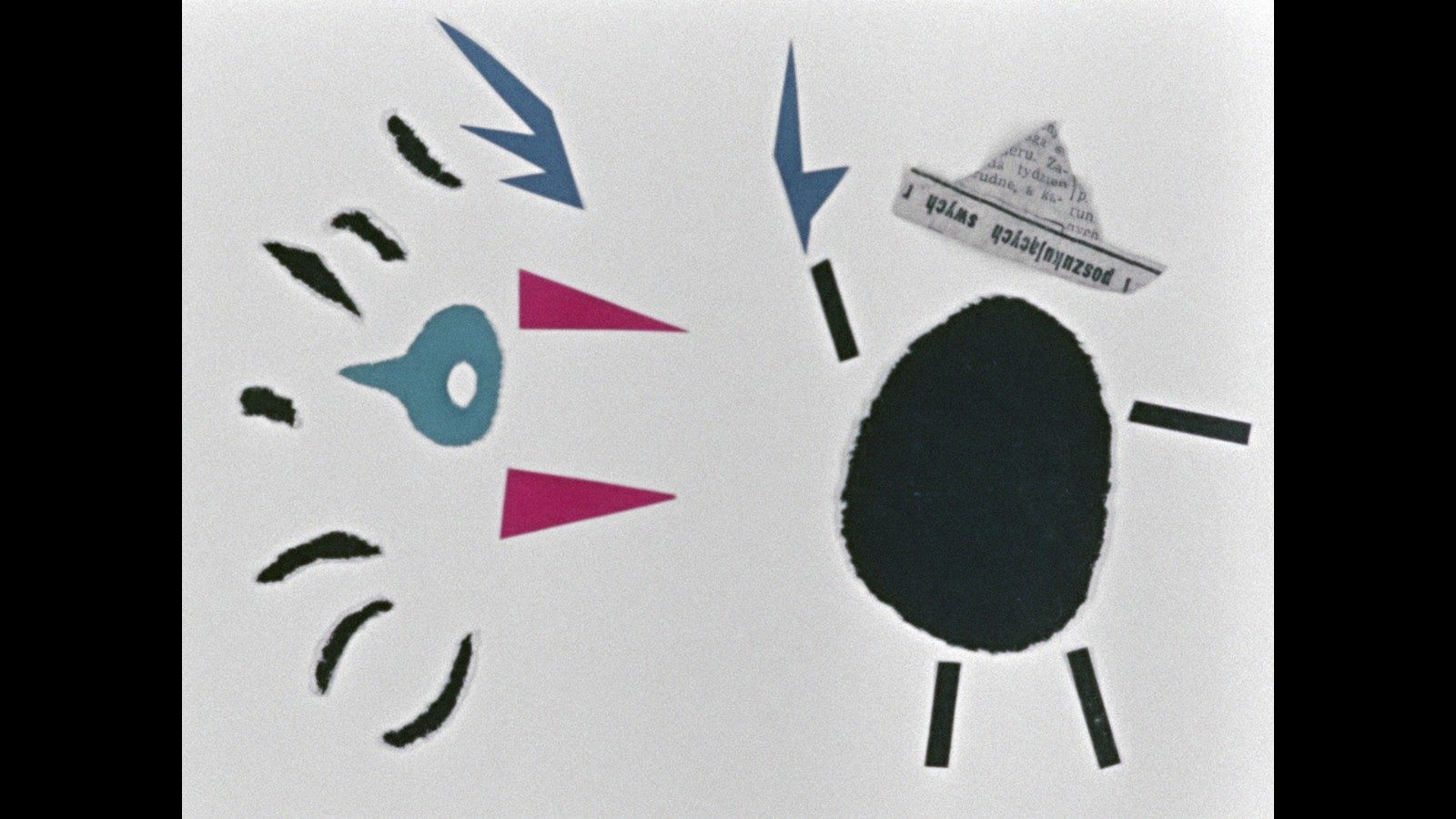

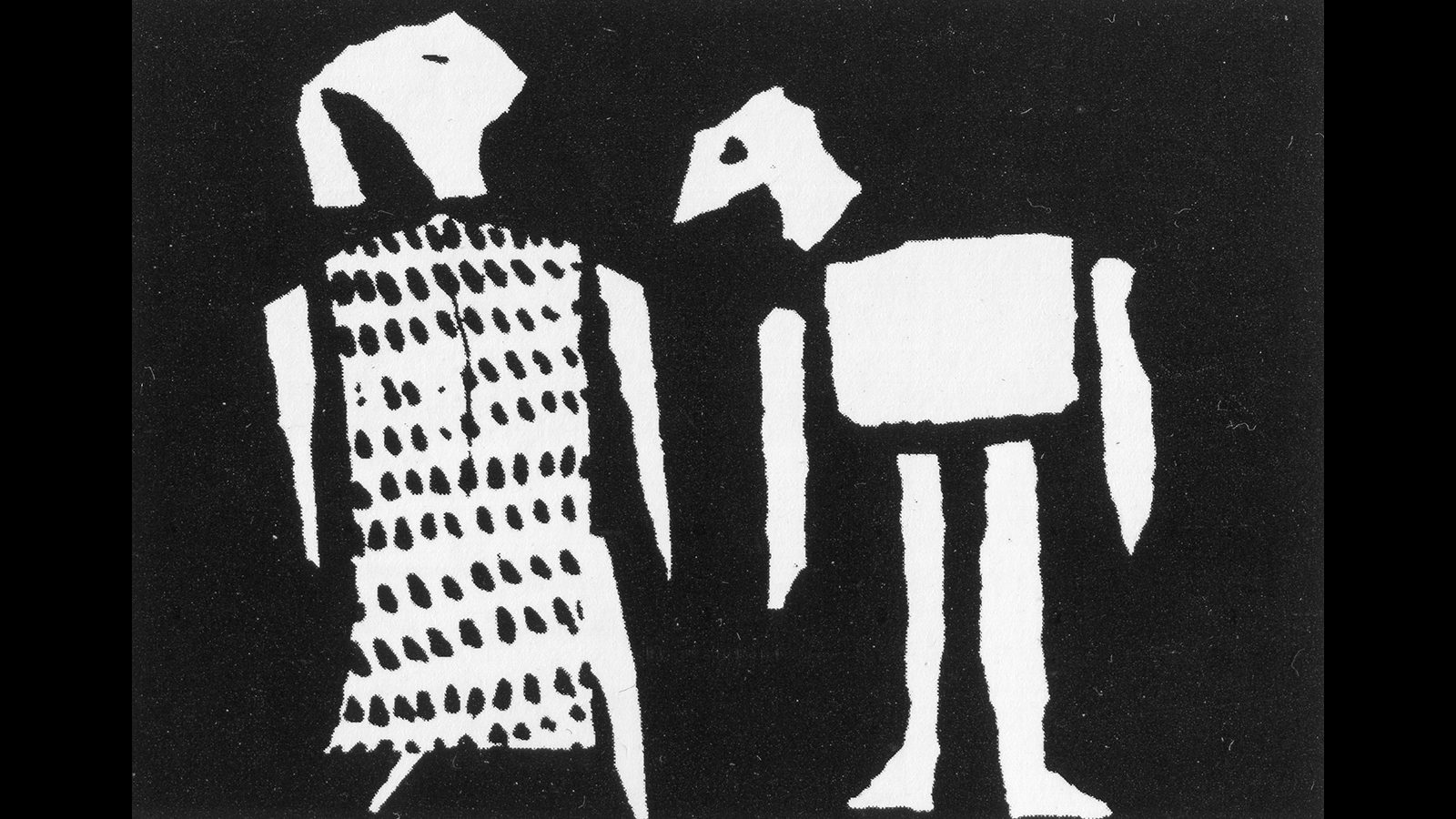

Once Upon a Time / Był sobie raz

Walerian Borowczyk & Jan Lenica, Poland, 1957, 9m

While not the first cut-out animation, this is without a doubt one of the most innovative. In effect, Borowczyk and Lenica transformed the economy, wit, and intelligence of the Polish poster into cinema. It is also notable for a groundbreaking electro-acoustic soundtrack courtesy of the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio.

Strip-Tease

Walerian Borowczyk & Jan Lenica, Poland, 1957, 2m

Borowczyk and Lenica are at their most expressive in this crude paper miniature.

Rewarded Feelings / Nagrodzone uczucie

Walerian Borowczyk & Jan Lenica, Poland, 1957, 8m

Borowczyk and Lenica’s second collaboration is a politically correct romance told through the paintings of Jan Płaskociński. Playful, witty, and ironic, Rewarded Feelings is augmented by a rousing score courtesy of the Warsaw Gasworks Brass Orchestra.

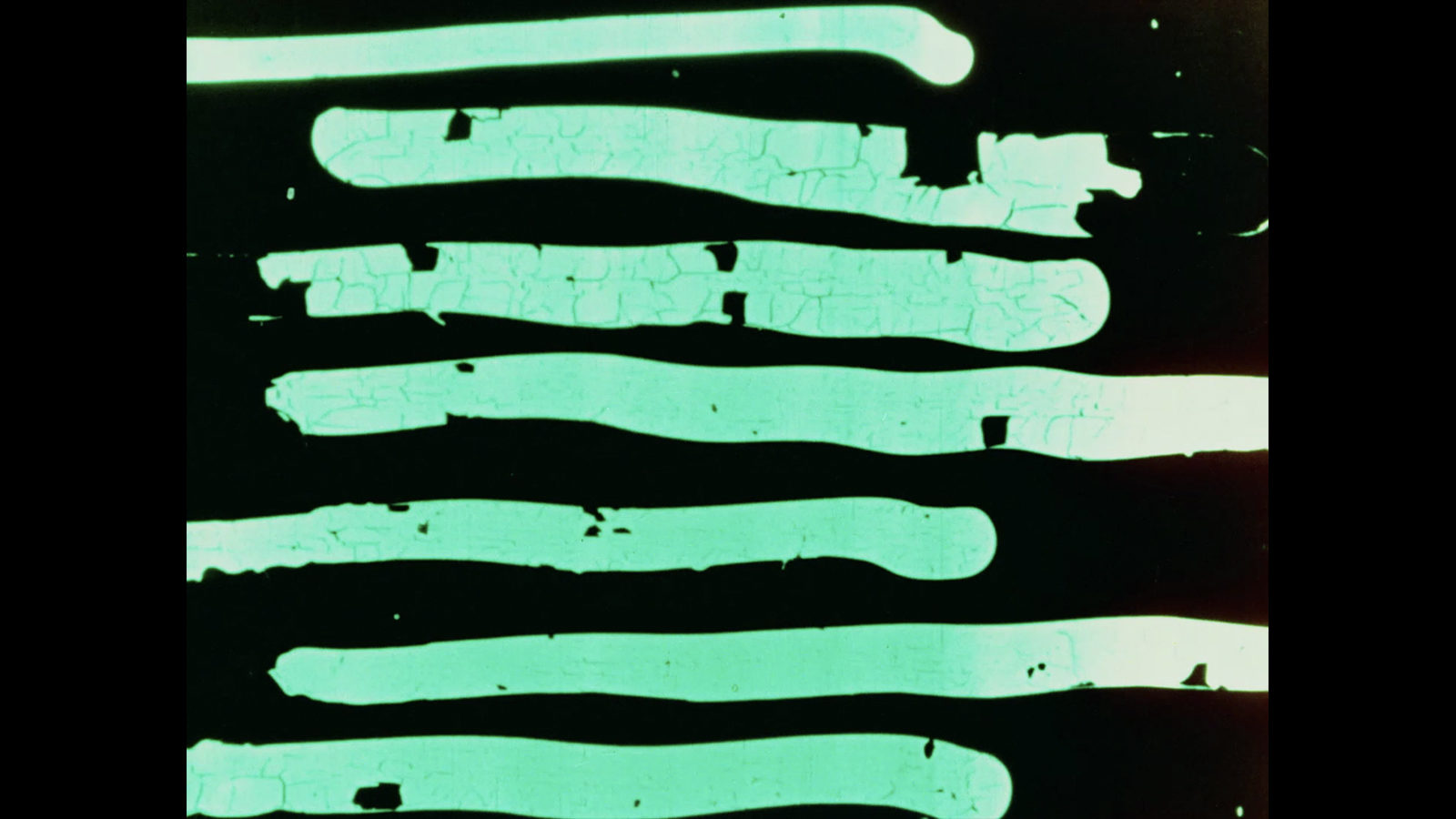

Banner of Youth / Sztandar mlodych

Walerian Borowczyk & Jan Lenica, Poland, 1957, 2m

In this miniature newsreel interlude made for the journal of the Polish Youth Union (ZMP), Borowczyk and Lenica recycle the montage of found footage in Once Upon a Time and add on a hand painted element.

The School / Szkoła

Walerian Borowczyk, Poland, 1958, 7m

In Borowczyk’s first solo outing as a director, a soldier is subjected to a series of increasingly ridiculous training maneuvers until finally retreating into daydreams and fantasy. The School is almost exclusively made up of photographs of actor Bronisław Stefanik ordered to create movement, recalling the innovation of Norman McLaren as well as early and pre-cinema techniques.

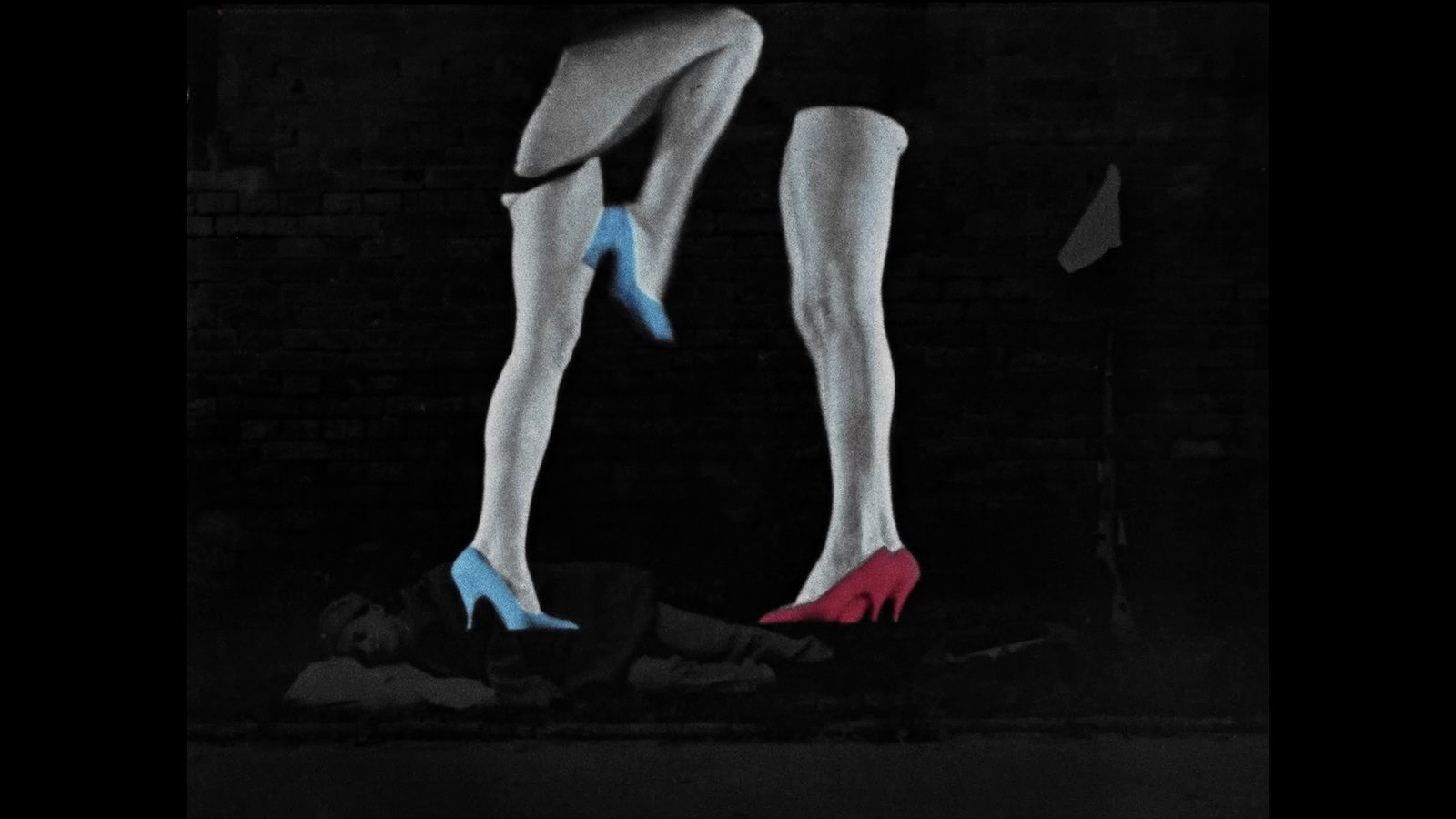

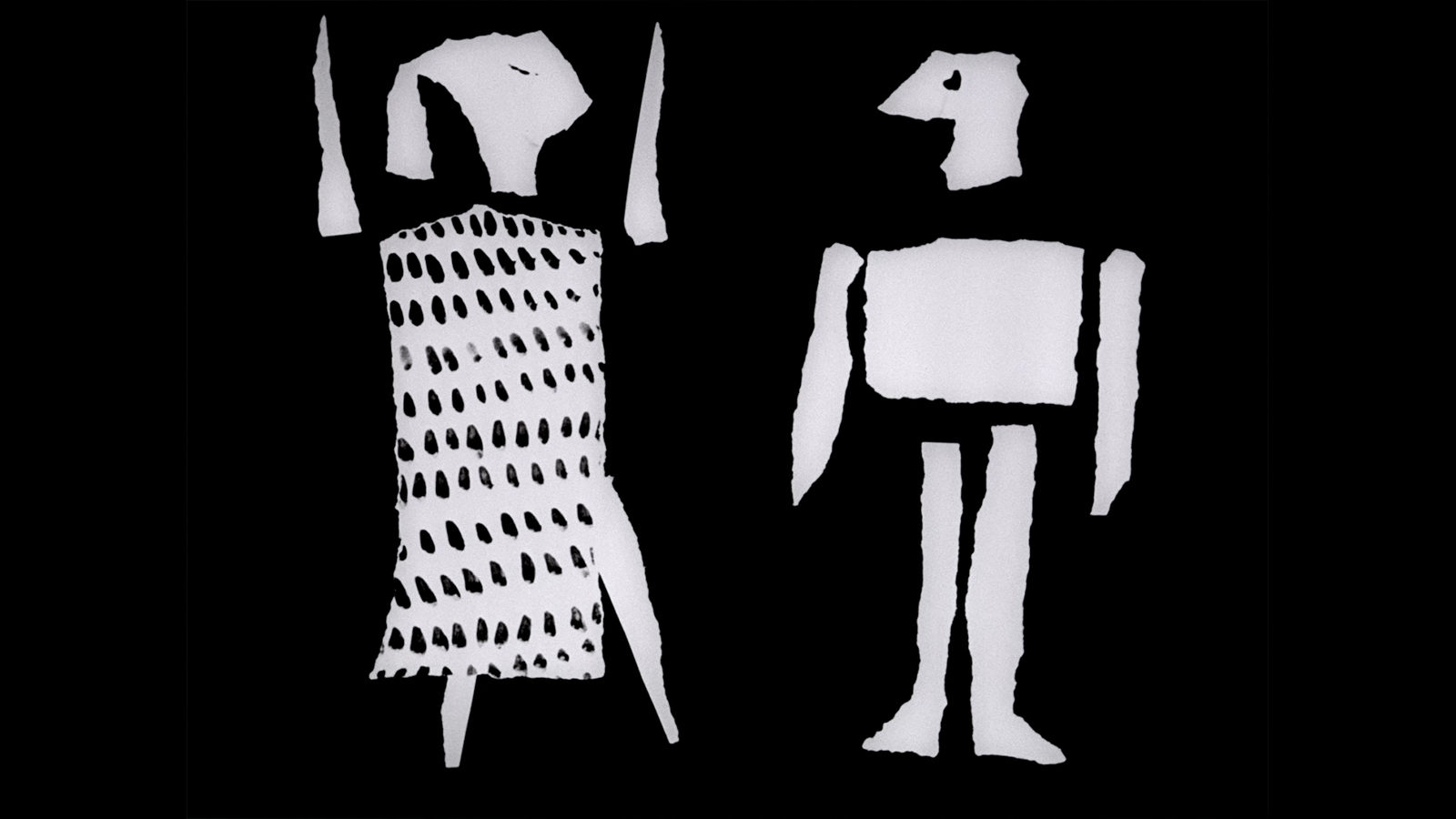

House / Dom

Walerian Borowczyk & Jan Lenica, Poland, 1958, 11m

A young woman inside a house succumbs to a succession of daydreams, fantasies, and nightmares. Arguably Borowczyk and Lenica’s masterpiece, House served as Borowczyk and Lenica’s ticket to the West. The result is a veritable compendium of animation techniques, which both look back at the European avant-garde of the 1920s (Cocteau, Richter, Ray, Ernst, Calder, Duchamp, etc.) while paving the way for the likes of latter-day Czech surrealist Jan Švankmajer. It also features a remarkable electro-acoustic soundtrack by Włodzimierz Kotoński.

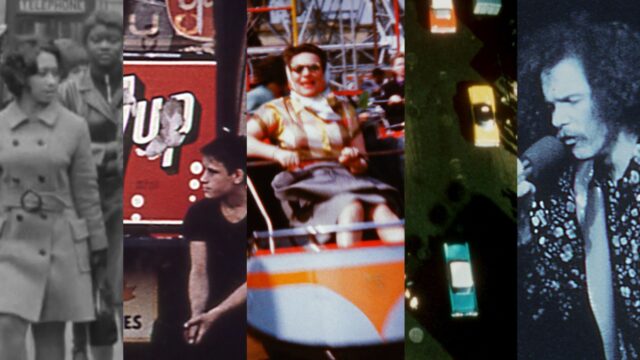

Street Art / Sztuka ulicy

Konstanty Gordon, Poland, 1957, 10m

Polish with English subtitles

Co-written by Borowczyk, Konstanty Gordon’s short newsreel documents Poland’s poster art scene in the late ‘50s.

Restorations by Fixafilm (Warsaw). Special thanks: WFDiF; Daniel Bird, Friends of Walerian Borowczyk.

Read a remembrance of Walerian Borowczyk by Szymon Bojko, the Polish art historian who also co-wrote Street Art, originally published in the catalogue of the 2006 Norwich International Animation Festival:

Walerian Borowczyk (aka Boro) was a graphic artist and motion picture virtuoso who seduced audiences with webs of hidden meanings, spanning dreams, history, mythology and eroticism. But this story has two heroes.

The demonic and incorrigible Boro grabbed critical and media attention for many years. He left behind a huge filmography and gained legendary status on the day he died. He was a mysterious figure, never looking for publicity, rarely giving interviews and failing to promote himself among producers. Boro despised media buzz and the constant pursuit of fame in a market of vanity and rejected all superficial trends. He hated unjustified criticism and treated ‘critics’ with reserve. The latter, not without reason, often accused him of arrogance and intolerance. He deliberately created the portrait of a withdrawn artist with an imagination that surpassed reality, tradition and memory. He trusted his intuition, feelings and analytical sense. His great sensitivity opened the door to the secrets of proto-human genetic instincts. Boro explored our animal nature like few others.

Był sobie raz… (Once Upon a Time, 1957), the young artist’s co-debut with Jan Lenica (who later gained international fame), is the film which stands out in my memory. The short was immediately noticed by international audiences and made its way into the pantheon of animation. Collage, montage, naïve lines and strokes, newspaper cuttings, humorous narrative. It stays fresh and compelling from the initial bouncy letters to the final stop-motion frame. Poetic and minimal, it appeals to viewers of all ages. Looking back at Był sobie raz…, one sees how the artist developed – from the bright and trustful to the darker sides of life. Both faces are his.

I met Walerian Borowczyk in the early fifties. When I remember him now, I realise I enter a realm clouded by a half-century of facts – akin to looking at worn and faded photos. Because of the gaps in Borowczyk’s biography, it’s worth reconstructing those memories, as each detail in his life is priceless and crucial to decrypting the various riddles, visions and imaginative heights.

Let me start with his physical description, which set him apart wherever he went. A stout, strong body, dense, woolly hair, a short neck and piercing eyes. It provoked anxiety and confusion. We met in Warsaw, and I was immediately puzzled by Borowczyk’s expressive gestures and glances, which could replace standard verbal communication. In attire, he was neat to the point of asceticism and minimalist in speech. He represented an intriguing form of introversion, was absent in conversation and enclosed in his own thoughts.

Boro spoke rarely but reacted enthusiastically to external stimuli. He thus transformed into another man, with an amazing cognitive inquisitiveness laced with erudition. His interrupted monologues were intertwined with names of scientists and inventors, and I was both amazed and confounded by his knowledge. During our cooperation on the script of Sztuka ulicy (Street Art, 1957; directed by Konstanty Gordon), I got closer to his way of thinking and was presented with one of his best kept secrets. It concerned Ligia, a film actress, his wife-to-be and heroine of Boro’s most erotic flicks. She was very young and extremely beautiful, with a tamed, quiet sensuality that indeed was hard to resist. Her sexual spirit was like that of de Sade’s salons. Socially unavailable, she rarely appeared in public alone, staying at the side of her alert husband.

Ligia then moved to France, where she turned actress and became the star of Borowczyk’s troupe. Even in their suburban Vésinet home and tabloid refuge, Ligia remained mysterious and ascetic, which so greatly contrasted her perverted on-screen roles, considered pornographic. The know-it-all film critics never even noticed Ligia – the very woman behind Borowczyk’s sexual energy and vision. Without the intuition of this traditionally educated girl, the liberated, sexually explicit erotic films would not have been created.

Walerian Borowczyk’s cinema of eroticism fell into conflict with the law and morality. Sex, however, was not the main motor of this art. Rather, it was driven by the ‘bestiary’ – the bestial essence of man. If he did violate morality, he did so on purpose. He trusted his senses, and his oeuvres uncovered beauty even in visions of the inappropriate.