Film at Lincoln Center announces New York, 1962–1964: Underground and Experimental Cinema spotlighting the rise of the New American Cinema, running from July 29–August 4.

1962 to 1964 was a pivotal moment in the evolution of American arts and culture, especially in New York City. These years, crucial to the development of Pop, Minimalism, and performance, saw the emergence of a new generation of radical artists, as well as venues that gave their iconoclastic work a home and a context. Movies, meanwhile, were undergoing a transformation of their own: the rise of a truly independent cinema, of works unencumbered by the medium’s aesthetic conventions and commercial imperatives.

“Cinema,” wrote Jonas Mekas in a 1962 Village Voice column, “is beginning to move. Cinema is becoming conscious of its steps. Cinema is no longer embarrassed by its own stammerings, hesitations, side steps. Until now cinema could move only in a robotlike step, on preplanned tracks, indicated lines. Now it is beginning to move freely, by itself, according to its own wishes and whims, tracing its own steps. Cinema is doing away with theatrics, cinema is searching for its own truth, cinema is mumbling, like Marlon Brando, like James Dean. That’s what this is all about: new times, new content, new language.”

FLC’s highly focused series, which coincides with the Jewish Museum’s upcoming exhibition New York: 1962–1964 (on view from July 22, 2022 to January 8, 2023), will feature key efforts by Kenneth Anger, Shirley Clarke, the Kuchar Brothers, Marie Menken, Jonas Mekas, Carolee Schneemann, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol, to name a handful. Join us as we look back on this richly varied—and still underappreciated—period of experimental cinema.

Film Forum’s “1962…1963…1964,” a related series of the fertile three-year period in cinematic history, will run from July 22–August 11.

Organized by Thomas Beard and Dan Sullivan. Co-presented with the Jewish Museum.

Special thanks to Ed Halter and Anthology Film Archives.

Tickets go on sale Monday, July 11 at noon with a FLC Member pre-sale beginning on Friday, July 8 at noon and are $15; $12 for students, seniors (62+), and persons with disabilities; and $10 for FLC Members. Become a member today! See more and save with a 3+ Film Package or All-Access Pass ($75 for general public and $35 for students). Learn more at www.filmlinc.org.

Film at Lincoln Center, the Jewish Museum, and Film Forum will offer reciprocal admission discounts to each other’s programs (with proof of purchase). Enjoy $11 tickets at Film Forum’s series with ticket stub from FLC’s series, available only at box office. Enjoy half-price admission to the Jewish Museum with ticket stub from related series, offer good from July 22, 2022 through August 14, 2022. To redeem discounted tickets, email [email protected] or call 212-423-3200.

FILMS & DESCRIPTIONS

All films will take place at the Francesca Beale Theater in the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center (144 W. 65th Street)

Program 1: Film-Makers’ Showcase

The Film-Makers’ Showcase. Credit: The Film-Makers’ Cooperative

Film-Makers’ Showcase

Francis Lee, 1963, 16mm, 3m

Jerry

David Brooks, 1963, 16mm, 3m

Divinations

Storm de Hirsch, 1964, 16mm, 6m

Notebook

Marie Menken, 1964, 16mm, 10m

Fleming Faloon

Owen Land, 1964, 16mm, 5m

Breath Death

Stan VanDerBeek, 1964, 35mm, 10m

Scorpio Rising

Kenneth Anger, 1963, 16mm, 29m

In January of 1962 the Film-Makers’ Cooperative was established as the distribution wing of the New American Cinema Group, with Jonas Mekas leading the charge. The Coop provided an influential model, replicated across the globe soon thereafter, for artists to come together and collectively oversee the circulation of their work. The variety of avant-garde film forms that the organization helped support is on view in this program, ranging from the cinematic sketches of Marie Menken’s Notebook and the hand-painted celluloid of Storm de Hirsch’s Divinations to the delirious collage of Stan VanDerBeek’s Breath Death and the masterful montage of Kenneth Anger’s homoerotic biker odyssey Scorpio Rising. “We don’t want false, polished, slick films—we prefer them rough, unpolished, but alive,” declared the New American Cinema Group in its first published statement later that year. “We don’t want rosy films—we want them the color of blood.”

Friday, July 29 at 7:00pm

Wednesday, August 3 at 6:30pm

Program 2: New Lines: Avant-Garde Animation

Fist Fight. Credit: Anthology Film Archives

Shoot the Moon

Rudy Burckhardt and Red Grooms, 1962, 16mm, 24m

Pat’s Birthday

Robert Breer, 1962, 16mm, 13m

Breathing

Robert Breer, 1963, 35mm, 5m

Fist Fight

Robert Breer, 1964, 16mm, 11m

Late Superimpositions

Harry Smith, 1964, 16mm, 31m

This program begins with Rudy Burckhardt and Red Grooms’s delightful Méliès homage Shoot the Moon, and proceeds to the work of Robert Breer, one of the most adventurous figures in the history of animation. Breer advanced the graphic possibilities of cinema in works like Breathing, with its dramatically metamorphosing lines, and the autobiographical Fist Fight, a rapid-fire progression of single-frame images, first shown as part of a production of Stockhausen’s Originale, that combines drawn elements alongside rephotographed stills. Late Superimpositions, meanwhile, overlays New York scenes with those of an ethnographic trip to Oklahoma, marking a departure for the polymath artist Harry Smith; it was his first foray away from the animation table, previously the primary site of his cinematic activity. “I honor it the most of my films,” noted Smith.

Friday, July 29 at 8:45pm

Wednesday, August 3 at 8:15pm

Program 3: Dorsky, Meyer, Markopoulos

Twice a Man. Credit: Beavers

Ingreen

Nathaniel Dorsky, 1964, 16mm, 12m

Shades and Drumbeats

Andrew Meyer, 1964, 16mm, 25m

Twice a Man

Gregory J. Markopoulos, 1963, 16mm, 49m

“I wish to demonstrate by the film Twice a Man, a new narrative form which is based on very brief film-phrases used in clusters to evoke thought through imagery,” Gregory J. Markopoulos wrote in an essay about his modern restaging of the Hippolytus myth. By intercutting these fleeting moments into longer sequences, he found novel ways to convey the shape of consciousness via cinema, highlighting the psychological and aesthetic force of individual film frames, and the space between them. Beyond the innovations of his approach to composition, Markopoulos was also a tremendously supportive and influential figure for young gay experimental filmmakers in the 1960s, such as Robert Beavers, Tom Chomont, Jerome Hiler, Edward Owens, and Warren Sonbert, as well as Nathaniel Dorsky and Andrew Meyer, represented here by important early works.

Saturday, July 30 at 2:00pm

Thursday, August 4 at 4:00pm

Program 4: Screen Tests + Blow Job

Blow Job

Screen Tests [Reel 16: Paul America, Susan Sontag, Lou Reed, Ruth Ford, Harold Stevenson, Henry Rago, Nico, Alan Soloman, Jack Smith, Ethel Scull]

Andy Warhol, 1964–66, 16mm, 30m

Blow Job

Andy Warhol, 1964, 16mm, 41m

Andy Warhol produced hundreds of screen tests—each the length of a single 100-foot roll of film—in his studio between 1964 and 1966. The subjects of these studies included some of the most significant artists, writers, and filmmakers of the period, as well any number of Factory denizens who have slipped through the cracks of art history. The Screen Tests, Callie Angell once argued, “may be viewed as a series of allegorical documentaries about what it is like to sit for your portrait, with each poser trapped in the existential dilemma of performing as—while simultaneously being reduced to—his or her own image.”

Blow Job, a film far more frequently alluded to than actually seen, bears some correspondence with these works. It, too, silently frames a single face with a stationary camera, though for far longer, and with the eponymous act being performed off-screen. There is an extraordinary beauty to the close-up of Blow Job, the figure’s reactions slowed down by the silent-speed projection, but the film has also been noted as a clever provocation: a sex film that visibly elides sex, thereby frustrating porngoers and vice squads alike.

Saturday, July 30 at 4:15pm

Program 5: Blonde Cobra + Flaming Creatures

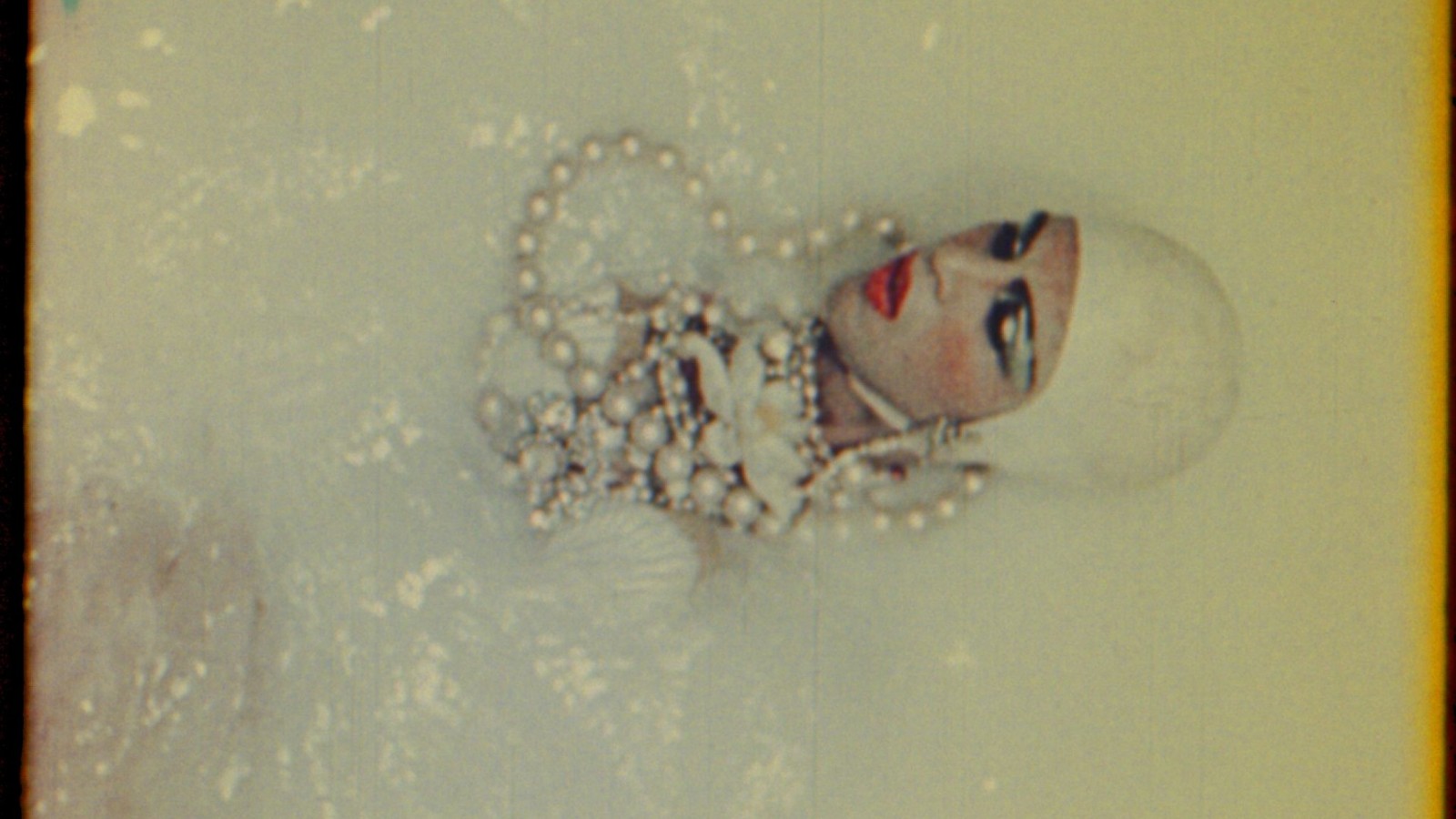

Flaming Creatures. Credit: The Film-Makers’ Cooperative

Blonde Cobra

Ken Jacobs, 1963, 16mm, 33m

Flaming Creatures

Jack Smith, 1963, 16mm, 43m

Jonas Mekas, along with Ken and Flo Jacobs, was arrested for screening Flaming Creatures in 1964, and the obscenity case that followed would become a central episode of the New American Cinema. The film’s images, idiosyncratically framed and etherealized by the outdated stock they were shot on, feature the extravagantly costumed sybarites of the title as they dance, preen, and, most strikingly, take part in a pansexual mock orgy. “Flaming Creatures is that rare modern work of art: it is about joy and innocence,” wrote Susan Sontag. “To be sure, this joyousness, this innocence is composed out of themes which are—by ordinary standards—perverse, decadent, at the least highly theatrical and artificial. But this, I think, is precisely how the film comes by its beauty and its modernity.”

Assembled from audio of Smith that Jacobs recorded, and images drawn from two aborted film projects shot by Bob Fleischner, Blonde Cobra stands as one of the great documents of Smith as a performer. “It’s a look in on an exploding life,” said Jacobs, “on a man of imagination suffering pre-fashionable Lower East Side deprivation and consumed with American 1950s, ‘40s, ‘30s disgust. Silly, self-pitying, guilt-structured and yet triumphing—on one level—over the situation with style, because he’s unapologetically gifted, has a genius for courage, knows that a state of indignity can serve to show his character in sharpest relief. He carries on, states his presence for what it is. Does all he can to draw out our condemnation, testing our love for limits…enticing us into an absurd moral posture the better to dismiss us with a regal ‘screw-off.’”

Saturday, July 30 at 6:15pm

Thursday, August 4 at 6:30pm

Program 6: Normal Love

Normal Love. Credit: The Film-Makers’ Cooperative

Normal Love

Jack Smith, 1963, 16mm, 120m

A noted influence on Mike Kelley and Andy Warhol, among many others, Jack Smith was a consummate artist’s artist, and Normal Love is one of his most remarkable achievements. Made in the wake of his succès de scandale Flaming Creatures, the film is a dimestore fantasia, rendered in a palette of voluptuous pinks and greens. Smith channels the cult actress and camp touchstone Maria Montez while riffing on the iconography of old monster movies, resulting in a thoroughly stylized, Dionysian romp. “Normal Love,” the critic J. Hoberman once noted, “is sumptuous but static—in part because Smith never completed editing it. Rather, he exhibited Normal Love rushes and rough cuts through 1965, and thereafter showed excerpts in various combinations with different sorts of exotic musical accompaniment as a projection-performance piece. Thus, like Sergei Eisenstein’s unfinished ¡Que viva México! and various Orson Welles projects, Normal Love’s extant 135 minutes can only exist as a presentation of footage.” Yet this footage is singular, and the images it contains—drag legend Mario Montez as a bejeweled mermaid lounging in a milk bath, revelers swaying atop a Claes Oldenburg cake—are not soon forgotten.

Saturday, July 30 at 8:15pm

Program 7: Film and Performance

Meat Joy. Credit: © Estate of Carolee Schneemann / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY. Image courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

Happenings: One

Raymond Saroff, 1962, 16mm, 23m

Meat Joy

Carolee Schneemann, 1964, 11m

Chumlum

Ron Rice, 1964, 16mm, 26m

Christmas on Earth

Barbara Rubin, 1963, double 16mm, 30m

This program includes Raymond Saroff’s Happenings: One, an invaluable record of the ten “happenings” staged by Claes Oldenburg in an East Second Street storefront; Meat Joy, Carolee Schneemann’s seminal work of filmed “kinetic theater,” in which the nude bodies of eight performers meld with an assortment of materials (paint, paper, art tools, raw meat, poultry, and fish) in a confrontation with social taboos and cultural repression; Ron Rice’s Chumlum, a polychromatic, texturally rich dreamwork featuring the cast of Jack Smith’s Normal Love; and Barbara Rubin’s Christmas on Earth, a major work of expanded cinema that uses a double-16mm projection and live radio to conjure, in Rubin’s words, a “cross-section of psychic tumult.”

Sunday, July 31 at 2:00pm

Program 8: Merce Cunningham + The Brig

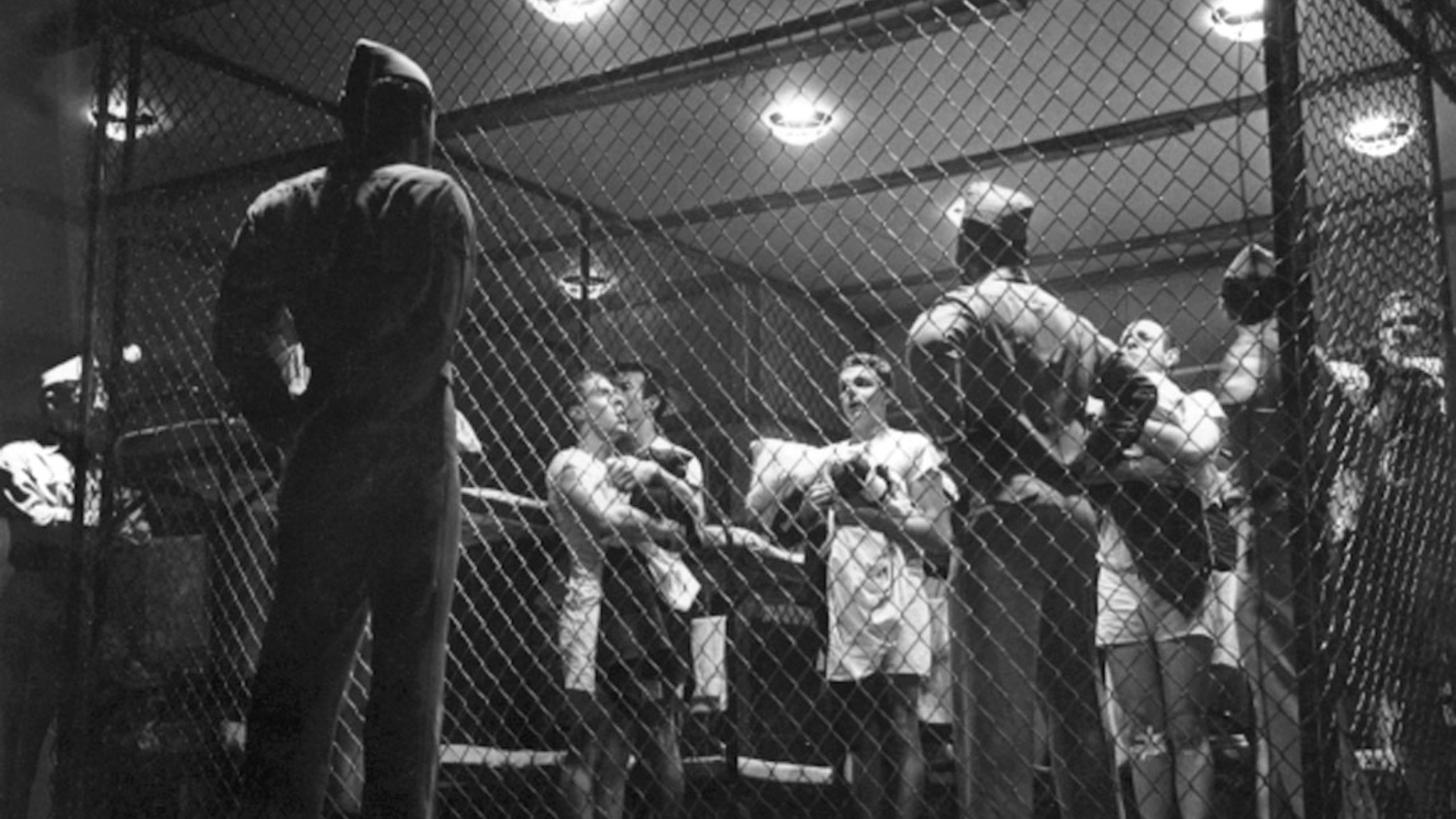

The Brig. Credit: The Film-Makers’ Cooperative

Merce Cunningham

Jackie Raynal, 1962, 16mm, 27m

The Brig

Jonas Mekas, 1964, 16mm, 68m

Jonas Mekas looked to the stage for his second feature, an adaptation of Kenneth H. Brown’s play of the same name, which had been produced off-Broadway at the Living Theatre by Judith Malina and Julian Beck. A harrowing, suffocating portrait of brutality and dehumanization within a Marine Corps prison, the film chronicles the abuses and indignities suffered by 10 prisoners at the hands of a few sadistic guards across a single day. At once a distinctive translation of experimental theater and a fierce polemic against the conjoined carceral and military apparatuses, the film is marked by “a nightmare air that suggests Kafka with a Kodak,” as a Time write-up at the time of its premiere put it. A selection of the 1964 New York Film Festival. Screens with Jackie Raynal’s Merce Cunningham, her film portrait of the choreographer as he collaborates with Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage, providing a contrasting view of performance in New York from the same period.

Sunday, July 31 at 4:15pm

Program 9: Eye and Ear Control

New York Eye and Ear Control. Credit: Canyon Cinema

The Last Clean Shirt

Alfred Leslie, 1964, 40m

Peggy’s Blue Skylight

Joyce Wieland, 1964, 16mm, 12m

New York Eye and Ear Control

Michael Snow, 1964, 16mm, 34m

This program includes: Alfred Leslie’s The Last Clean Shirt, a collaborative experiment (with poet Frank O’Hara) in cinematic parallelism, in which a black man and a white woman drive around downtown Manhattan; Peggy’s Blue Skylight, Joyce Wieland’s document of a day in the loft she shares with her then-husband Michael Snow as a succession of friends visit; and Snow’s own New York Eye and Ear Control, in which a group of free jazz musicians (Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, John Tchicai, Roswell Rudd, Gary Peacock, Sonny Murray) provide accompaniment for a series of images featuring the artist’s iconic Walking Woman silhouette. “The film,” wrote Snow, “contains illusions of distances, durations, degrees, divisions of antipathies, polarities, likenesses, complements, desires. Acceleration of absence to presence. Scales of ‘Art’-’Life,’ setting-subject, mind-body, country-city pivot. Simultaneous silence and sound, one and all.”

Sunday, July 31 at 6:30pm

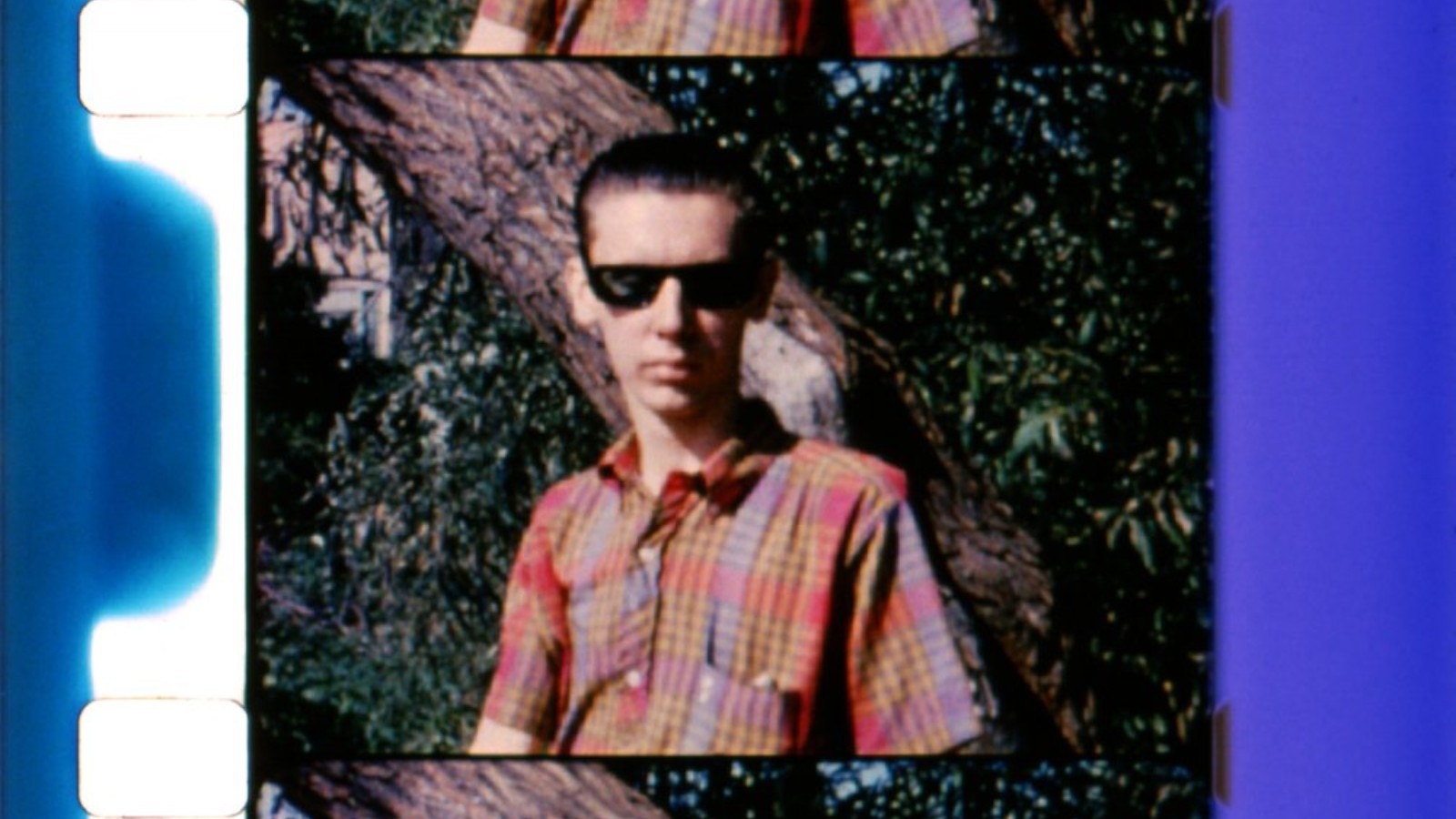

Program 10: Meet the Kuchar Brothers

A Town Called Tempest. Credit: © Kuchar Brothers Trust

Tootsies in Autumn

George and Mike Kuchar, 1963, 16mm, 12m

A Town Called Tempest

George and Mike Kuchar, 1963, 16mm, 33m

Lovers of Eternity

George and Mike Kuchar, 1964, 36m

George and Mike Kuchar entered the underground as Bronx teenagers who were making visionary 8mm approximations of Hollywood spectaculars, providing, in the process, a kind of roadmap for the camp-punk stylings of later auteurs like John Waters. This program, comprised of three early efforts by the duo, includes: Tootsies in Autumn, wherein a group of past-their-prime stage actors descend into madness as they fight and bicker amongst themselves; A Town Called Tempest, a typically torrid melodrama concerning extreme weather conditions; and the tragicomic Lovers of Eternity, in which a lonesome hipster poet makes friends with a succession of bizarre characters atop a squalid New York rooftop in a latter-day Garden of Eden, complete with a cast featuring Jack Smith, filmmaker Dov Lederberg, and an enormous cockroach. A Town Called Tempest is preserved by Anthology Film Archives through the Avant-Garde Masters program funded by The Film Foundation and administered by the National Film Preservation Foundation. Tootsies in Autumn and Lovers of Eternity are preserved by Anthology Film Archives with support from the National Film Preservation Foundation.

Sunday, July 31 at 8:45pm

Program 11: Hallelujah the Hills

Hallelujah the Hills. Credit: The Film-Makers’ Cooperative

Hallelujah the Hills

Adolfas Mekas, 1963, 82m

Inspired as much by Hollywood comedies and romances of the silent era as by the French New Wave, Adolfas Mekas’s debut feature remains, 59 years after its American premiere in the first New York Film Festival, an irreverent delight, a semi-slapstick vision of true love, and a valentine to cinema itself. Two madly impulsive young men are in love with the same woman, who happens to be played by two different actresses. The snow-covered fields and trees of Vermont gleam brilliantly in the background in this film that prompted Jean-Luc Godard to write, in Cahiers du Cinema, that Mekas is “a master in the field of pure invention, that is to say, in working dangerously—‘without a net.’” A selection of the 1963 New York Film Festival.

Friday, July 29 at 2:00pm

Tuesday, August 2 at 6:30pm

Wednesday, August 3 at 4:00pm

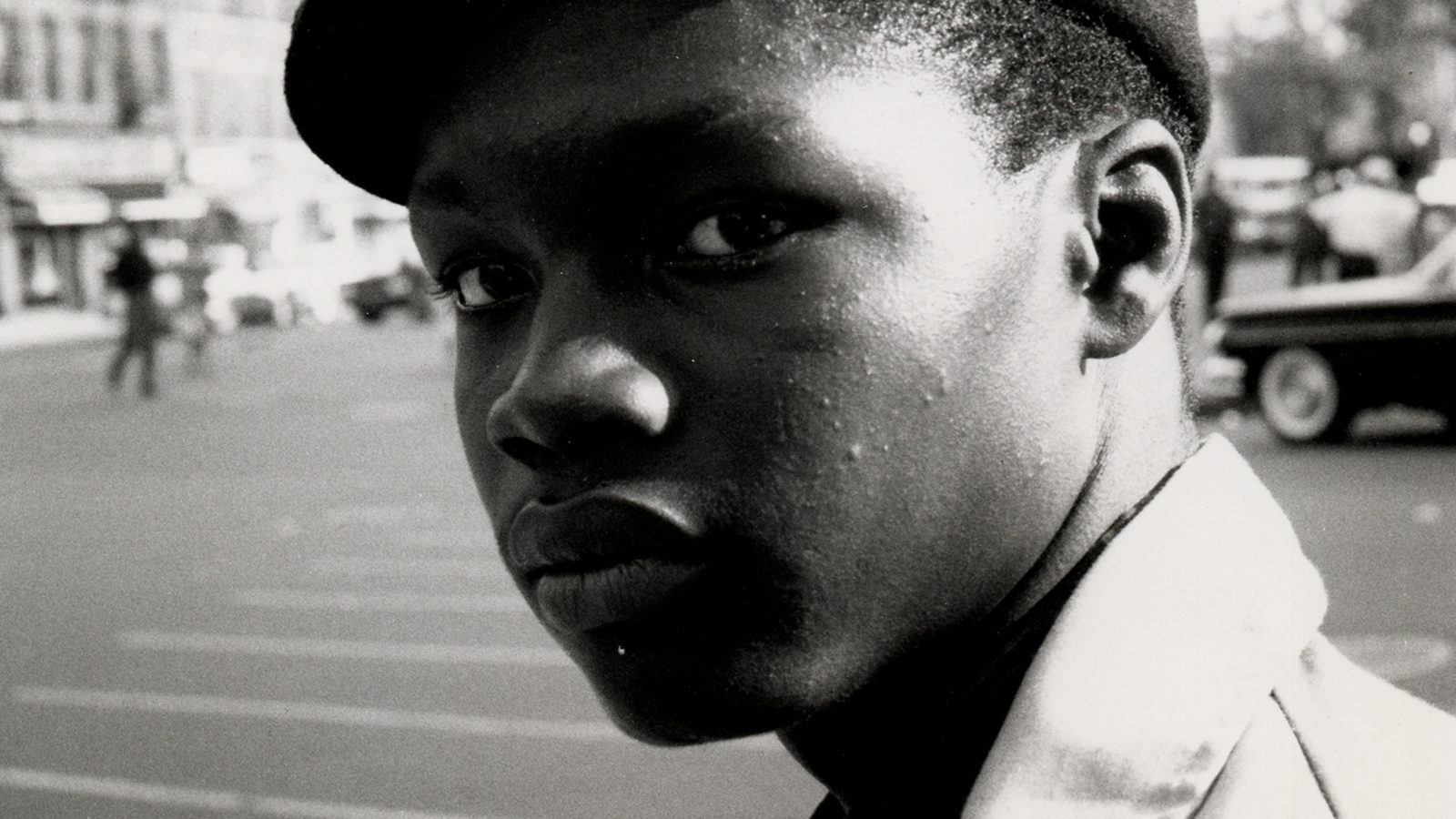

Program 12: The Cool World

The Cool World. Credit: Zipporah Films

The Cool World

Shirley Clarke, 1964, 35mm, 125m

Based on the novel by Warren Miller about a teenager navigating the violent turf wars and internal hierarchies of Harlem gangs, and set to an unforgettable jazz score composed by Mal Waldron and performed by Dizzy Gillespie, Shirley Clarke’s The Cool World is a landmark of early American independent cinema. The film was produced by a young Frederick Wiseman, and it possesses something of a documentary quality as a result of its uptown location shooting, cast of local non-actors, and partially improvised performances. “Everything I’ve done,” Clarke explained late in her career, “is based on the duality of fantasy and reality,” and The Cool World, like many of the works in this series, is constantly pivoting between the two.

Friday, July 29 at 4:00pm

Tuesday, August 2 at 8:30pm

Thursday, August 4 at 8:30pm