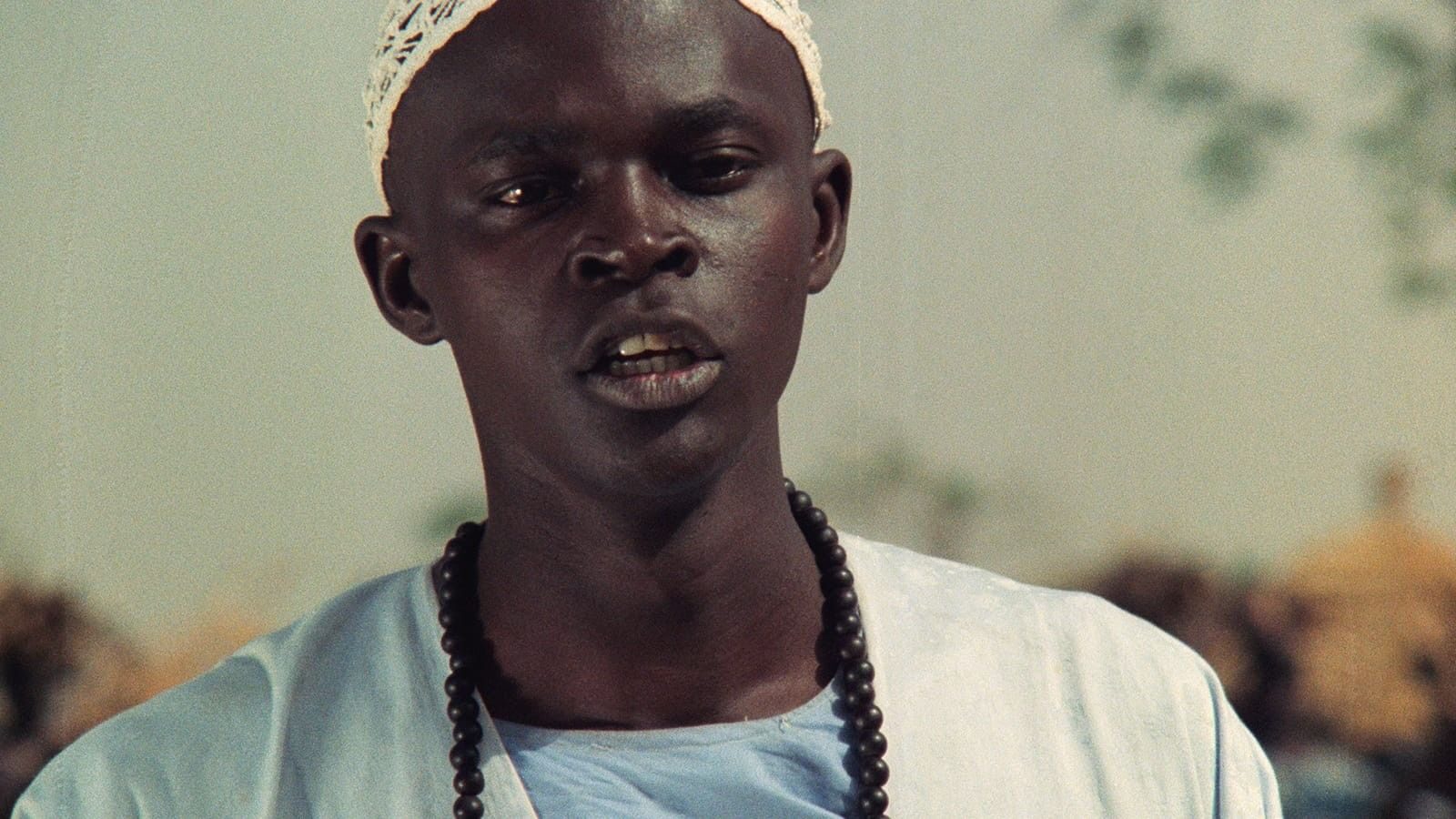

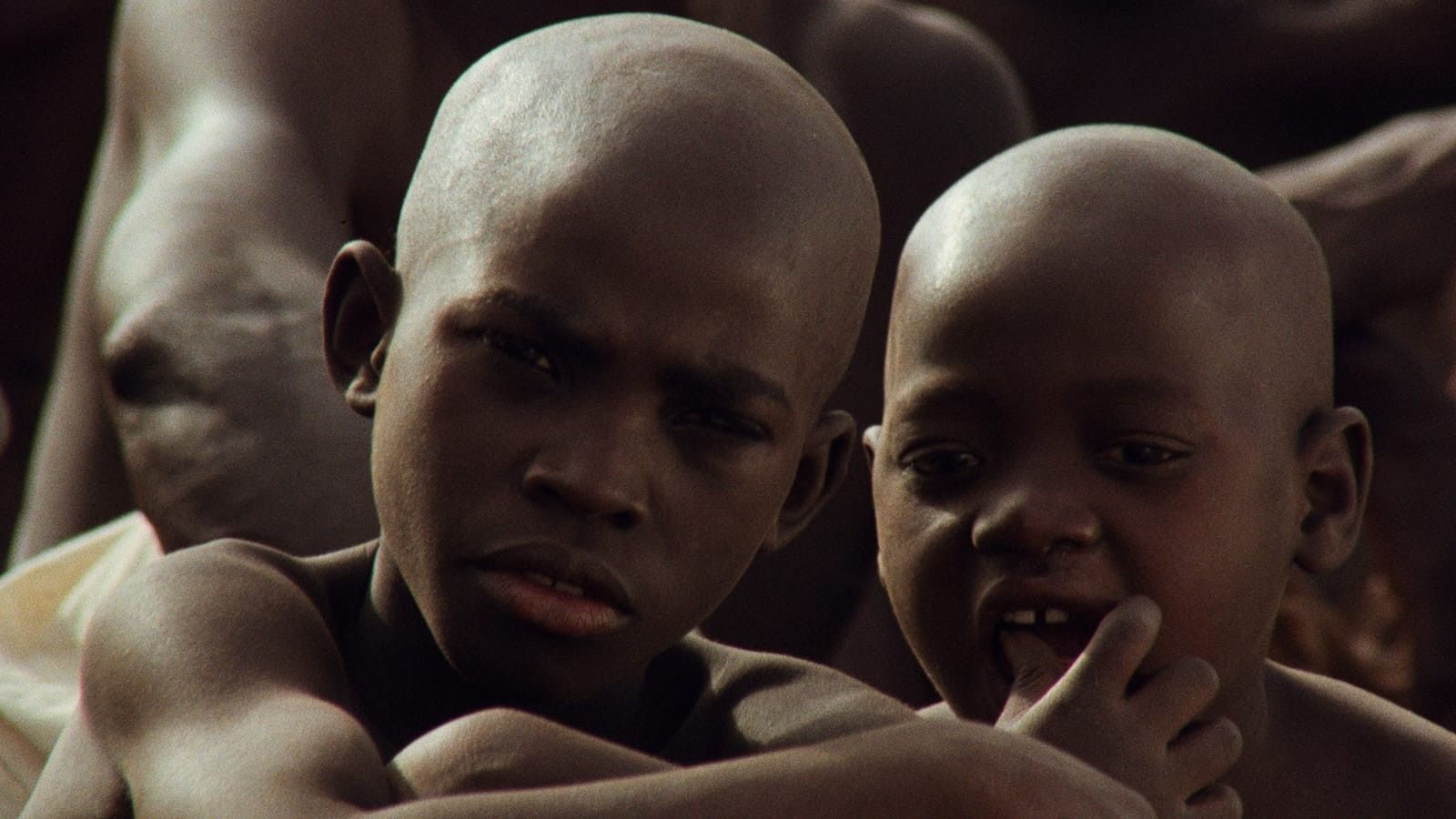

Ceddo

Ousmane Sembène, the pioneer of feature filmmaking in Senegal, explores the effects of colonialism on his country in this sui generis blend of ritual, folklore, and history. Set across multiple indeterminate time periods, the film traces the conflict that emerges as the Ceddo—the common people—struggle to preserve their way of life against the slave trade and the invading influences of Christianity and Islam, even after the conversion of their own king and the kidnapping of his daughter, princess Dior Yacine. In this politically sophisticated, visually stunning film, the role of the princess is not as a damsel in distress, but as an emblem of the resistance that was at the heart of Sembène’s work. Indeed, like many of his films, Ceddo was banned in its own country, allegedly due to a linguistic disagreement between Sembène and then president Léopold Sédar Senghor over the title: by insisting Ceddo retain double consonants, Sembène refused to follow the newly mandated Wolof standard of spelling. Writing on what he saw as Sembène’s most beautiful film, Serge Daney was sensitive to this question of language: “An account of a putsch, with the intrusion of religion into politics and the passage from one type of power to another, Ceddo is also the story of the loss of a right: the right to speak.” In his description, Ceddo sounds both timeless and terrifyingly contemporary.