Native Land + The Forgotten Village

Native Land

Leo Hurwitz, 1942, USA, 35mm; 80m

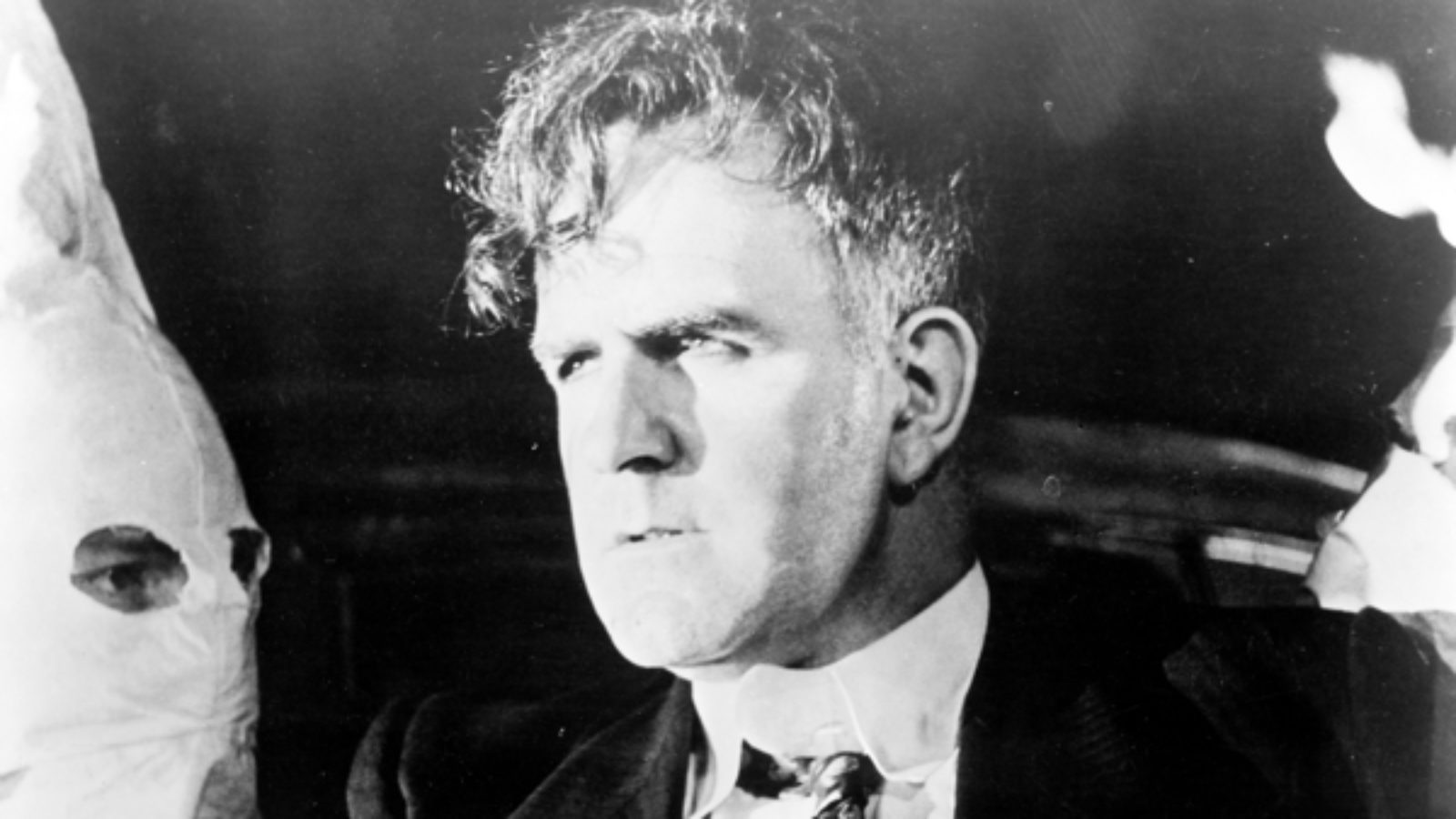

The controversial docudrama by Paul Strand and Leo Hurwitz is a strikingly shot and fluidly edited essay on patriotism, intolerance, and class struggle, mingling reenactment and newsreels.

Paul Strand and Leo Hurwitz’s independently produced docudrama, Native Land, was politically more radical than anything Strand had ever done, yet the film also continues Strand’s exploration of man and nature. Its troubled production history (1937-1941), due to a chronic lack of funds, was further compounded when The Hitler-Stalin Pact, then World War II negatively impacted the film’s reach and effectiveness. Initially based on the United States Senate’s LaFollette Committee on Civil Rights Hearings on labor union busting and corporate labor spying, the script by Ben Maddow and the directors became a paean to the growth of the American labor movement. Constructed out of documentary and newsreel sequences as well as fictional footage using professional actors to reenact events, the film opened commercially in May 1942 and quickly disappeared, its message of class struggle no longer in tune with the national unity politics of the home front in World War II.

The film opens with a series of images of waves crashing against the rocky cliffs of a primordial land. In the following shots Strand cuts from the sea to the forest to majestic mountains, to rivers. With Paul Robeson’s strong voice booming on the soundtrack, the film develops a surprisingly patriotic narrative of man struggling for freedom, given it’s leftist ideology. Yet the development of cities and civilization alienates man ever further from nature. Powerful political and economic interests exploit the land and its people, as demonstrated in powerful sequences of racism, intolerance, and corporate thuggery. Certainly an ideological hybrid in its time, the film’s striking black and white cinematography is supported by fluid editing that mark the filmmakers as students of Eisenstein and Pudovkin.

—Jan-Christopher Horak, director, UCLA Film & Television Archive

Preserved from the original 35mm nitrate picture negative, a 35mm safety duplicate negative, and a 35mm safety up-and-down track negative. Laboratory services by The Stanford Theatre Film Laboratory, NT Picture and Sound, and Audio Mechanics.

screening with

The Forgotten Village

Herbert Kline, 1941, USA, 35mm; 67m

Preservation funded by The Packard Humanities Institute.

John Steinbeck once remarked that most documentaries concerned large groups of people but that audiences could better identify with individuals. In his first work written for the screen and his only screen documentary (actually more of a docudrama told in the form of a parable), Steinbeck concentrates on one symbolic family. An indigenous couple, Ventura and Esperanza, live with their six children in the small and remote pueblo of Santiago, somewhere on the central plateau of Mexico. The film focuses on their oldest son, Juan Diego, who attempts to bridge two very different worlds, one traditional and one modern. Through an idealistic young teacher at the government school in his village, Juan Diego is introduced to modern science. As an outbreak of a mysterious disease begins to affect his family and the village around him, Juan Diego struggles to overcome ancient superstitions and tries to save his small community from suffering and death.

Steinbeck became involved in the project when friends introduced him to Herbert Kline, a distinguished young director who had recently directed four anti-fascist documentaries. Steinbeck wrote what he called an elastic story that could be stretched to fill the circumstances the film team found when they moved into a real back country village. The Forgotten Village was filmed in the states of Puebla and Tlaxcala, Mexico for $35,000, using a non-professional cast of mostly indigenous residents of the region. As none of the villagers could speak Spanish, much less English, a narrator was used to tell the story. Originally, Spencer Tracy was to do the narration, but, at the last moment, MGM reneged on releasing him from his contract. He was replaced by Burgess Meredith.

The film was to have had its world premiere on September 9, 1941 at the Belmont Theatre in New York City. In August, the New York State Board of Censors refused to license the film for public exhibition, objecting to a child birth scene that it characterized as “indecent” and “inhuman”. Luckily, the ban was overturned on appeal, and the film opened, uncensored, at the Belmont Theatre on November 18, 1941. It opened to good reviews and a modest box office, but, unfortunately, Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into the war diffused its impact.

— Jeffrey Bickel, newsreel preservationist, UCLA Film & Television Archive.

screening with

News of the Day (April 3, 1941)

1941, USA, 35mm; 9m

Preservation funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Picture preserved from original 35mm nitrate printing negative; sound preserved from a 35mm nitrate composite print. Laboratory services by Film Technology, Inc.