Program 6: At Sundance

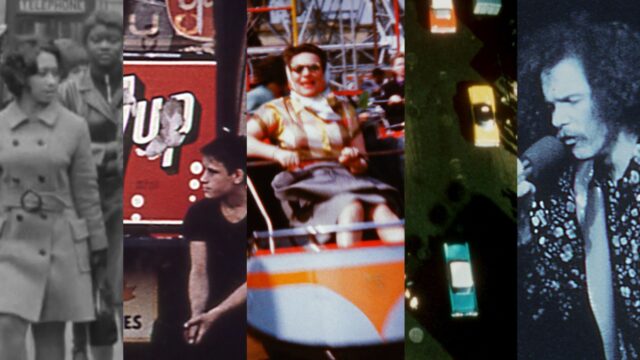

It’s January 1995, cinema’s centenary has commenced, and Michael Almereyda and Amy Hobby are at Sundance with a Pixelvision camera, asking their fellow filmmakers about the future of movies: Are they optimistic, or pessimistic? Replies vary. Edward Burns sees the possible audience for independent cinema increasing, with moviegoers more inclined toward Terminator now encountering trailers for art-house productions. Todd Haynes is more guarded, noting how audiences seem less adventurous than before, not more so; gone, he explains, are the days when people would line up around the block to see Chelsea Girls. Some bemoan the perpetual grind of publicity and financing, while others beam about the vocabulary of moviemaking expanding apace. For Haskell Wexler, the question is ultimately a political one: whether the future for film is bright or dim depends upon the future of the world and its citizens. Like Wim Wenders’s Room 666, which pursued a similar line of inquiry at Cannes in 1982, At Sundance has become a captivating artifact, a document of its time yet still thoroughly unresolvable and therefore contemporary.

Programmer Thomas Beard on Pixelvision, the “Underappreciated Flipside of ’90s Indie Cinema”:

I bought a PXL 2000 on eBay years ago, back when I was in college, but unfortunately I could never get it to work. The Pixelvision camera was kind of legendary, a plastic camcorder for kids put out by Fisher-Price in the late ’80s that recorded its ghostly, low-res images onto a regular audio cassette. As a toy, the PXL 2000 was rather a bust, yanked from the shelves after only a year—they were too expensive, they were temperamental—but the story of Pixelvision doesn’t end there. It had a look like nothing else, a dreamy visual texture, fuzzy as a faded memory, and the format had a surprise second act in the hands of experimental filmmakers, who used the device to shoot some truly remarkable movies, like Michael Almereyda’s Nadja, a wry riff on the vampire picture, or Sadie Benning’s teenage bedroom tapes, which, in my estimation, are among the most moving and imaginative records of queer adolescence ever made.

Over the years there have been a number of one-off Pixelvision screenings, but nothing this comprehensive, and many of the titles aren’t currently available on DVD or Netflix, so if you’re intrigued by the curious afterlife of the PXL 2000 and the challenging, strangely beautiful films it captured, now’s the time to check them out. Think of this series as the underappreciated flipside of ’90s independent cinema.