Tommy Guns

Q&A with Carlos Conceição on April 8 and 9

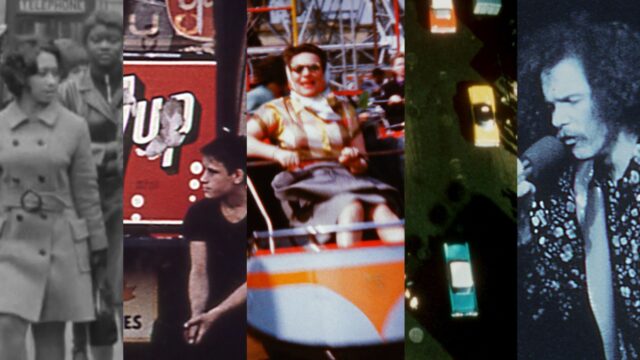

With his eccentric, shape-shifting breakthrough, Carlos Conceição confidently announces his arrival as a daring filmmaker preoccupied with the colonialist legacy of his native country. Set in 1974 Angola, during the waning days of Portugal’s militaristic rule over the African nation, the film jumps between different perspectives, including those of local rebels and villagers contending with the persistence of authoritarian forces and the occupying soldiers who occasionally use the weapons of the title with indiscriminate force. Yet the film also vaults among genres and modes with audacity, constantly reinventing itself with elements of war drama, comedy, and supernatural horror. An unexpected reflection on historical tyranny and the metaphysical effects of war retold as a tale of nightmarish resurrection, the jolting Tommy Guns was the winner of the Best European Film award at the 2022 Locarno Film Festival. A Kino Lorber release.

What made you first want to be a director?

Carlos Conceição: It was a while until I could put it into words, but I guess the main reason why I started creating films was to originate testimonials, depictions of humanity that might outlive me as factual direct imagery, in opposition to, say, literature. I think cinema is the most important tool for the preservation of time.Was there a film or director you were inspired by or continue to be inspired by?

There are few directors whose work speaks to me as a whole, except for someone like Jonas Mekas, who is his own work. I like many films by Antonioni for its modernity, for its dramatic portrayal of ennui as the main disease of contemporaneity. I also like early Pasolini because he is the opposite: a myth maker who dwells on the pursuit of the sublime, often over rocky paths. Finally, David Cronenberg is the ultimate satirist, someone who has created images and hidden meanings that have lingered with me throughout my own apprenticeship. I also love Akira Kurosawa, who is probably the only one who somehow is an influence on my film. And the silent masters: Murnau, Lang, Dreyer.In your own words, tell us about your film. What should audiences know?

For many reasons, the less an audience knows about my film before they see it, the better. One factor above all is very important to me: that the film is understood as a reflection on the danger of bringing back certain political ideas that should (and must) remain in the past.What does it mean to you to show your film at New Directors/New Films?

A privilege to show my film at a festival for real cinephiles who will be there for the love of cinema above anything else. Also, an honor to have my work included in such a selective curator-ship.What was the biggest lesson you learned during the making of your film?

To be patient and keep cool. There is a lot of stress involved in a shoot and there are few things as ridiculous as an hysterical director. Also, every single person in a team needs respect and a signal of empathy from the director. This is more of a principle than it was ever a lesson. If I have to pick a lesson, I will say it is very important to trust your own instincts and not let creative hesitations cripple the process. Also, you shouldn’t really get advice from more than two people.What is the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given?

When it comes to filmmaking, every advice I was ever given proved useful once and a total limitation afterwards. In life, I like the expression “If it ain’t broke don’t fix it”, even though it’s sort of silly.What else do you enjoy doing outside of filmmaking?

Reading and writing, spending time with animals, and – especially when I’m abroad – discovering new artists.What’s a film you saw recently that you enjoyed?

Rodrigo Sorogoyen’s The Beasts, Owen Kline’s Funny Pages, and Albert Serra’s Pacifiction, all from 2022.