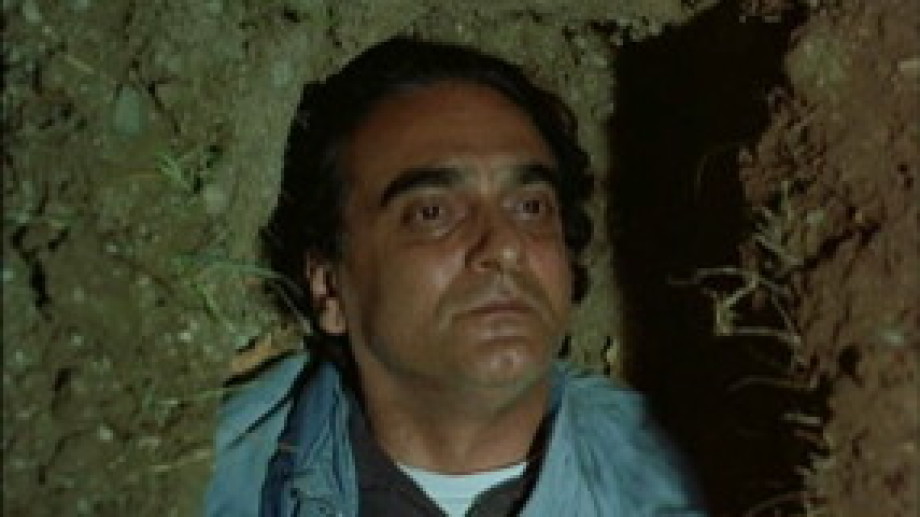

Homayon Ershadi as Mr. Badii in Abbas Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry (NYFF '97). Photo courtesy of the Kobal Collection.

Scholars have theorized that, in film, cars can be seen as physical embodiments of Freud’s “death drive.” One might readily associate this with Abbas Kiarostami’s Palme d'Or-winning Taste of Cherry (NYFF '97); after all, it is a film in which a man drives around looking for someone to bury him after his planned suicide. But in Taste of Cherry, and other films from Kiarostami, the car is less a psychological device than it is a philosophical battleground in which characters—not of differing backgrounds, necessarily, but of differing ideals—are forced into debate.

While Kiarostami’s Ten, his 2002 film that also takes place largely within the confines of a car, shrieks and shrills, Taste of Cherry whispers. Quite possibly the loudest moment of the film is its opening scene, in which migrant laborers attack the protagonist's car like buzzards, seeing the man's searching eyes as a sign of his desperation for some sort of help. And they’re not completely wrong.

Kiarostami constantly plays with the audience's understanding of a film, most specifically by leaving out what we think of as necessary details. It isn’t until twenty minutes of driving around that we find out what the protagonist is looking for. Even the protagonist himself is a bit of a mystery. Why has he decided to end his life? As he tells one of the men he picks up, “it wouldn’t help you to know and I can't talk about it.” We don't even know his name; he's known to us simply as Mr. Badii.

Yet, despite the lack of background information, one can’t help but become invested in the story, due largely to the strengths, and the manipulation, of the performances. With such limited space, the actors didn’t have a chance to perform with each other. As the editor of the film, Kiarostami shifts the emotional weights of scenes and makes the most of the medium with his simple stylistic decisions—mainly, his tendency to not cut on dialogue. Even when he does so, the conversation is almost never perfectly back and forth. The director's inclusion of pauses before responses, or sometimes a total lack of response, serves a much deeper aspect of the film. Not only do we become invested in Mr. Badii, we get caught up in the lives of his passengers or, to use a more appropriate term, his interviewees.

To be exact, there are three interviewees in the film. The first, a young solider; then a middle-aged seminarian; and lastly, an elderly taxidermist. The range in their responses to Badii's request is worth noting. The solider resolutely rejects Badii. The seminarian doesn't refuse, but offers to eat with him instead. The taxidermist immediately agrees, but tries to dissuade Badii from committing suicide. Kiarostami probes the notion that with age comes a deeper understanding of despair. The taxidermist admits he, too, thought of suicide once. He likens life to a “train that keeps moving forward and then reaches the end of the line, the terminus. And death waits at the terminus.” Instead of presenting this moment inside the vehicle, we hear it as we watch the car ebb along the desert mountains from afar.

As grim as the film may appear, in the end it becomes a minimalistic meditation on how to navigate the depths of despair. Badii isn’t racing towards death; he, like the film itself, moves gingerly. Maybe he’s moving slow enough for someone to save him.

Combine tonight's screening of Taste of Cherry with a meal at Indie Food and Wine in our Film Center with our unbeatable Dinner and a Movie deal for just $25! And make sure to check out the rest of the 50 Years of the New York Film Festival lineup, including next Tuesday's screening of Hou Hsaio-Hsien's exquisite Flowers of Shanghai (NYFF '98), films by Mike Leigh, Terence Davies and more!

Below is a list of films that played alongside Taste of Cherry at NYFF '97. Taste of Cherry was preceded by The House is Black, a haunting 1962 short by the great Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad, now considered a major touchstone for the Iranian New Wave:

The Ice Storm

Ang Lee, USA, 1997.

The Sweet Hereafter

Atom Egoyan, Canada, 1997.

Live Flesh

Pedro Almodóvar, Spain, 1997.

The Apostle

Robert Duvall, USA, 1997.

Boogie Nights

Paul Thomas Anderson, USA, 1997.

Deep Crimson

Arturo Ripstein, Mexico/France, 1996.

Destiny

Youssef Chahine, Egypt/France, 1997.

Fallen Angels

Wong Kar-Wai, Hong Kong, 1995.

Fast, Cheap & Out of Control

Errol Morris, USA, 1997.

From Today Until Tomorrow (Du jour au lendemain)

Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, France/Germany, 1996.

Hana-Bi (Fireworks)

Takeshi Kitano, Japan, 1997.

Happy Together

Wong-Kar Wai, Hong Kong, 1997.

Kiss or Kill

Bill Bennett, Austrailia, 1997.

Kitchen

Yim Ho, Hong Kong, 1997.

Love and Death on Long Island

Richard Kwietniowski, USA/Canda, 1997.

Marcello Mastroianni: I Remember

Anna Maria Tatò, Italy, 1997.

Martin (Hache)

Adolfo Aristarain, Argentina/Spain, 1997.

Ma vie en rose (My Life in Pink)

Alain Berliner, Belgium/France/UK, 1997.

Mother and Son

Aleksandr Sokurov, Germany/Russia, 1997.

Post Coitum, Animal Triste

Brigitte Roüan, France, 1997.

Public Housing

Frederick Wiseman, USA, 1997.

The Saragossa Manuscript

Wojciech Has, Poland, 1965. (NYFF Retrospective)

Telling Lies in America

Guy Ferland, USA, 1997.

La vie de Jésus

Bruno Dumont, France, 1997.

Voyage to the Beginning of the World

Manoel de Oliveira, Portugal/France, 1997.

Washington Square

Agnieszka Holland, USA, 1997

Orphans of the Storm

D.W. Griffith, USA, 1921.

“Logic of Dream, Logic of Labyrinth: The Fantastic Journeys of Wojciech Jerzy Has” (NYFF Retrospective)

Year of the Horse

Jim Jarmusch, USA, 1997.

The Kingdom, Part 2

Morten Arnfred and Lars von Trier, Denmark, 1997.