The Films of Keisuke Kinoshita

Buy tickets to two films together and save with our Double Feature package!

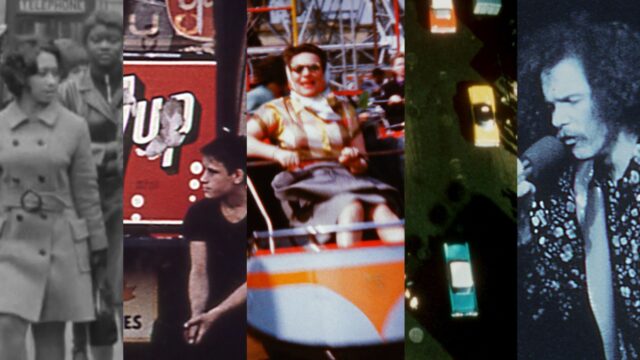

Universally considered one of the greatest Japanese directors, Keisuke Kinoshita, whose centenary we celebrate with this series, worked almost his entire career for Shochiku, the Japanese studio that also housed Yasujiro Ozu. Shochiku was that studio most devoted to what the Japanese call shomin-geki, stories of everyday life; yet while Ozu developed a rigorous, austere style that he perfected from film to film, Kinoshita was constantly changing, challenging himself to adapt to new subject matter and ways of storytelling. The director of Japan’s first color feature film, the charming musical satire Carmen Comes Home, could move just a few months later on to the bold experimentation just a few months later of A Japanese Tragedy, a work whose jumbled timeframe and insertion of newsreel footage anticipates the modernist films of the Sixties. He made bold use of traditional Japanese art forms such as kabuki (The Ballad of Narayama) and brush painting (The River Fuefuki), but could just as easily indulge in a steamy melodrama (Woman).

Kinoshita moved into the director’s chair after a traditional apprenticeship at the studio, and his familiarity with the many technical aspects of filmmaking led to his demanding the greatest effort from his crews. His two wartime films are forthrightly ambiguous in their view of militarism, and the arrival of the American occupation forces with their promotion of “democratic” ideals in the cinema suited Kinoshita perfectly. Perhaps the major theme that runs through his work is the loss of innocence: one character, usually the protagonist, at some point comes up against the harsh realities of the world. This emphasis on the individual, and his or her ability to craft their own choices, gave the early postwar films a progressive tine, but one can also sense the darkening of his vision as he moves into the Sixties. Although an early proponent for change in Japan, Kinoshita was clearly a man out of step with the vastly different country that had strayed from its traditions far more than anyone has ever imagined, as one can see in his final masterpiece, the remarkable The Scent of Incense.

It should also be said that Kinoshita was a terrific director of actors, and several—Kinuyo Tanaka, Hideo Takamine, Yuko Mochizuki, Keiji Sata—gave some of their greatest performances in his films.

This series was organized in collaboration with Shochiku and with the support of the Japan Foundation. Special thanks also to the Criterion Collection. Series programmed by Richard Peña.

Army

Kinoshita’s beautiful, subtle critique of Japanese militarism starts the great Kinuyo Tanaka as the mother of a sick young man called up for service.

The Ballad of Narayama

Fusing the ancient art of kabuki with modern cinema, Kinoshita creates an unforgettable account of a village in which the old are sent to a mountaintop to die.

Carmen Comes Home

A successful Tokyo stripper decides to pay a visit to her country roots in Kinoshita’s delightful musical satire, Japan’s first color film and still a great favorite there.

Farewell to Spring

Five young men return to their hometown and reminisce about their past as a way of confronting their present in Kinoshita’s bittersweet tale of lost opportunities and optimism.

Here’s to the Young Lady

A rising automobile magnate from a humble background is lured into a marriage with the daughter of a now penniless aristocrat in Kinoshita’s unpredictable social comedy.

A Japanese Tragedy

Bar hostess Haruko sacrifices everything to provide for her two children, who repay her with rebuffs and indifference, in Kinoshita’s ground-breaking study of postwar Japan.

Port of Flowers a.k.a. Blossoming Port

A pair of misfit con men try to hustle money from some unsuspecting townsfolk in Kinoshita’s droll, touching debut feature.

The Portrait

Kinoshita films a Kurosawa screenplay about a woman who decides to completely change her life after seeing a truthful painting of herself.

The River Fuefuki

Designed to resemble a scroll painting, Kinoshita’s handsome medieval period epic traces a farm family’s gradual succumbing to the military spirit.

The Scent of Incense

Raised by a prostitute mother, a young woman panics when she fears her fiancé will discover her dark family secret.

Thus Another Day

Disappointed with her husband’s behavior at work, a woman heads to the countryside in search of a Japan that’s fast disappearing.

Twenty-Four Eyes

Kinoshita’s portrait of a progressive schoolteacher (the great Hideo Takamine) and her students over 20 years of tumultuous Japanese history is widely considered the director’s masterpiece.

Wedding Ring

Kinuyo Tanaka and Toshiro Mifune square off in this touching melodrama about a successful businesswoman who falls in love with the doctor treating her ailing husband.

Woman

A dance-hall girl goes to meet an old lover at a seaside hot spring resort, only to discover that behind this rekindled passion lies a deadly secret, in Kinoshita’s inventive re-working of melodrama.

You Were Like a Wild Chrysanthemum

A mother’s ambition for her son forces him to break up with the one true love of his life in Kinoshita’s raving film on memory and desire.